I came to Indiana University to teach photography after a variety of positions including police photographer in Kalamazoo and Head of Photographic services at George Eastman House in Rochester.

One of the reasons I accepted a position at Indiana was the excellent reputation of its graduate photography program, the second oldest in the country, with many famous alumni including Jerry Uelsmann, Jack Welpott, Betty Hahn, etc. I succeeded Henry Holmes Smith, the legendary teacher who wrote brilliantly about photography as art at a time when it was not at all accepted as such.

At Indiana we have been fortunate to have worked with a steady stream of students who have gone out into our field and moved it forward as artists and teachers. The thing I am proudest of is that the vast majority have continued to make their own work years after grad school whether they have taken positions as educators or professional photographers. I could compile a similar list of our undergraduates who have gained admission to top grad schools and/or made careers as photographers, museum professionals, etc. They’ve won Fulbright Fellowships; received internships at places like Magnum Photo; George Eastman House; Art Institute of Chicago; ICP; etc. I have been blessed to have been able to work with and guide so many talented and ambitious young artists.

© Jeffery Wolin, ‘Tina with New Tatoo, Pigeon Hill / Tina after the Fire, Middle Way House’, (1991/2013), (2013). From the series Pigeon Hill - Then and Now

But the thing that has kept me at Indiana over the years has been the tremendous support the institution provides so that I can continue to make and exhibit my work. I am a photographer first and an educator second. I have been given financial resources as needed to undertake and complete my long-term projects. I am given the gift of time by way of a favorable teaching schedule and sabbatical leaves. Photography has helped shape my life and given it meaning. It has provided me with a source of income and a measure of my experiences.

Although I spent my first two years in college studying math and science, I graduated from Kenyon with a major in English literature, concentrating in particular on American literature from Herman Melville to Kurt Vonnegut. Another influence on my work is film. In college I was introduced to the classics of cinema—Bergman, Fellini, Truffaut. So the idea of narrative and art runs deep in me. And I had access to an old Chandler & Price printing press and kind of taught myself the basics of letterpress, printing books of poetry by authors I admired.

I went to RIT because I thought it would be the best place to combine my interest in photography and book making. They started me off in Typography 1 and I worked my way through all the classes in book arts they offered from history of typefaces to papermaking and bookbinding. My thesis was a handmade book of my photographs and writings. I still love books of all kinds, even in the age of the Kindle.

© Aaron Siskind, American, (1903-1991)

While working on my thesis I got a job at the Eastman House as a photographer and printer. Somewhere in there I got promoted to Head of Photographic services and wound up staying for almost five years. I got to print Lewis Hine’s glass plate negatives, Alvin Langdon Coburn’s negatives, some of Aaron Siskind’s “Harlem Document”. And we had total access to the archives where I really encountered the history of photography. At the time my work was strongly influenced by Eugene Atget and especially the Man Ray collection of Atget at GEH. I went through old technical books in the library to figure out the gold-toned POP process that Atget used. I was working with large format cameras and making contact prints using sunlight. And I had the great good fortune to become friends w/ Andre Kertesz and to spend time with him for a few years before he died. He welcomed young photographers to his apartment above Washington Square Park in NY and shared his passion for photography and life with me.

But despite my love of narrative and photography I had pretty much bought into the late modernist approach to art, which dominated photographic circles at the time I was a student. Even though I had a literature background and some experience as a writer, I avoided linking my photography and writing at that point.

© Sister Gertrude Morgan, Jesus Christ The Lamb of God and His Little Bride, 1960

In 1985 or so, we had a show at our Fine Arts Gallery at IU of work by “folk” artists Howard Finster and Sister Gertrude Morgan. I loved the way they wrote their visions into the positive space of their drawings and paintings. I realized that was something I could try with my own photographs. And so I picked up a pen and violated the canons of modernist photography by violating the pictorial space of my photographs. I began with a portrait of my father, which was later purchased by MoMA, the Hallmark Collection (now at the Nelson-Atkins Museum), Houston Museum of Fine Arts and Indiana University Art Museum—so the entire edition of four wound up in good hands. It also confirmed my new direction.

And I began to explore memories of my youth searching for possible stories that I could combine with existing photographs that triggered recollections of key moments from my past. For example, after college I wound up in Europe studying photography in art school in Antwerp—it was my first formal art training. This was in 1972 and the war in Vietnam was still raging on. I made a photo/text piece using an x-ray of my head (the result of a basketball injury) that refers to steps my friends took to avoid Vietnam and the luck I had in a special lottery we all had to take part in to determine which of us would be drafted and which of us would be allowed to go on with our normal lives. The resulting image was a death mask that simultaneously signified my birth as an artist. It was acquired by Graham Nash—fitting since the music of Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young provides part of my mental soundtrack of this time period.

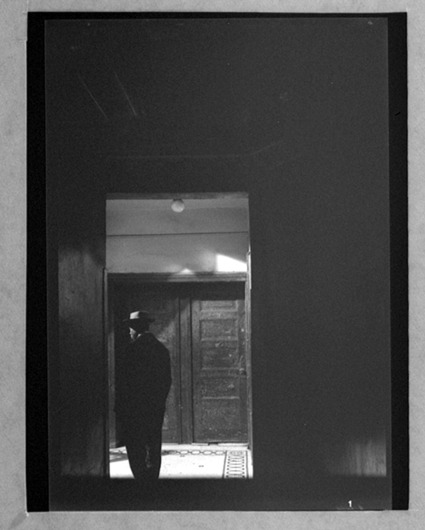

© Jeffrey Wolin, Police days, 1987

Another photo/text piece: After I returned to the US and before I went to grad school I got a job in the crime lab in the Kalamazoo police department. My two-year stint as a police photographer was quite formative (you can listen to the video 'Written in memory: Jeffrey Wolin at TED x Bloomington’ from here). At IU years later, I photographed the head of an executed murderer, which had been donated to the biology department at IU where I found it in a specimen room. The text, written directly onto the print, related several of the most tragic and gruesome things I had witnessed years earlier as a police photographer.

A few years after I arrived in Bloomington, Indiana to teach at Indiana University, an IU student named Ellen Marks was brutally killed. The murder took place on the west side of town, on a bluff known as “Pigeon Hill.” It contains the Crestmont Housing Projects for people who qualify for Section 8 housing. It is also the site of many small bungalows and shotgun shacks right out of Walker Evans’ “Let Us Now Praise Famous Men.” The legendary artist, Jerry Uelsmann, once told me he photographed up on the Hill when he first came to Bloomington to study photography in the ‘60’s. Jack Welpott did too.

© Jerry Uelsmann, Untitled (Pigeon Hill, Bloomington, Indiana), 1958-59

I used to pass the area when I drove to my car repair shop and when Ellen Marks was murdered I decided to explore Pigeon Hill with my camera. As I got to know the residents through my photographs, they would tell me more and more about their lives. I wrote their stories directly onto their portraits in silver or black ink. I became known for this particular style of combining image and text. And I had worked my way down from large format view cameras using natural light to medium format cameras with flash.

At the time I began photographing on Pigeon Hill, there was a lot of discussion about crime and poverty—it was the beginning of the crack epidemic. And there was a lot of talk about reforming welfare. I had something of a personal interest in this discourse: my father was born on the Lower East Side of Manhattan into extreme poverty. This was before the New Deal—there was no social safety net. He and his four brothers moved frequently with my grandmother from apartment to apartment when she couldn’t pay the rent. My dad was never able to overcome his humble origins even as he moved up in the world. I wanted to better understand the dynamic of poverty and how it affects people, especially children.

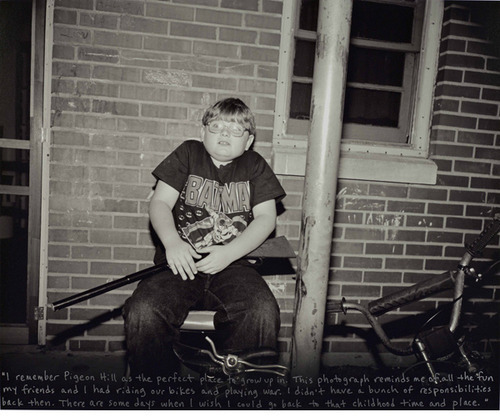

© “Tyke” Allen, Pigeon Hill, 1989

I admired the community aspects of the housing projects—people truly helped each other, knew their neighbors and helped raise each other’s kids. Everyone had large groups of friends and big extended families. But after a while I began to grow disillusioned about the prospects for the future of the people I had gotten to know, especially the children. Many teenagers were having children of their own and the cycles of poverty were being perpetuated. I needed to take a break from the series.

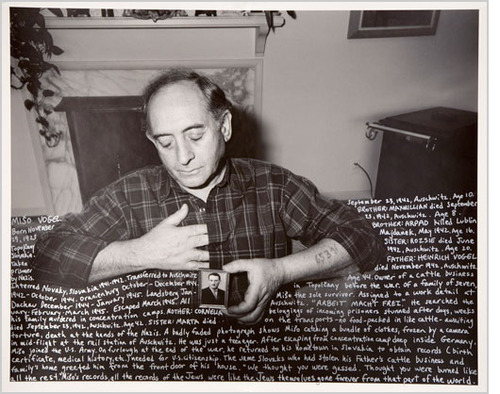

In 1991, I received a Guggenheim Fellowship for my photo/text work including the autobiographical pieces and the Pigeon Hill portraits. With a whole year off from teaching I decided to pursue two new projects: portraits of Holocaust survivors and portraits of Vietnam War veterans. I handled both the same way—I began each session with a videotape interview and then made portraits with my still camera trying to infuse aspects of the narrative into the visual structure of the photographs. By the end of that year, I decided to pursue the Holocaust survivor series and set aside the Vietnam War vets. The survivors were aging and dying and working with them seemed more pressing.

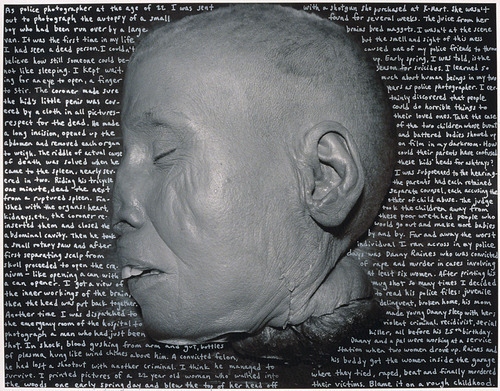

© Jeffrey A. Wolin from the series Written in Memory: Portraits of the Holocaust

In 1997, Chronicle Books published “Written in Memory: Portraits of the Holocaust” to accompany my exhibition which opened at ICP in New York and eventually traveled to the Art Institute of Chicago and other museums in the US as well as Zurich, Warsaw and Krakow. It became part of a larger traveling exhibition organized by Pierre Bonhomme of Paris that was shown in museums in France, Italy and Spain. The work began to resonate outside of art circles—e.g. I was the lead story on the 11 o’clock Polish national news—I got to see myself on TV with my voice dubbed into Polish. As a result I have no idea what I said to the Polish people. The President of Switzerland sent a long letter apologizing for not being able to attend my opening in Zurich. So it was interesting to see how that work interacted with the wider societies, due to its subject matter and the timing of internal political debates. I’ve always thought artists should engage as wide an audience as possible. It’s another reason I like to get my work out in book form in addition to exhibitions.

By 2003, I was ready to get back to the Vietnam veterans series. The war in Iraq, which had just broken out, probably spurred me on. I began to contact some of the veterans I had worked with a decade earlier. One had just died—he drank himself to death. Others had moved away. I located and re-photographed several and began to rebuild my contacts. And by now I was working with medium format color scanned to digital output.

I worked for a while with vets in and around Bloomington and then decided to expand the project, first, to the rest of Indiana; then to cities nearby, especially Chicago, and finally I worked with veterans from coast to coast: from New York to California and from Wisconsin to Alabama.

© Jeffrey A. Wolin, installation view 'Inconvenient Stories’, Museum of Contemporary Photography, Chicago

The exhibition, “Inconvenient Stories: Portraits of Vietnam War Veterans” opened at the Museum of Contemporary Photography in Chicago with an accompanying book by Umbrage Editions. Rather than writing directly on the prints as in earlier series, I made text panels with the war stories printed typographically to reference war memorials. Below is an incredibly moving story by John Linnenemeier, one of the vets I worked with who became a close friend. His story is filled with self-reflection on what it means at a fundamental level to be human and how war can force one to address the most primal issues of life and death and love. It is a story of healing and of reconciliation. His portrait contains visual references to travel, to the passing of time and spirituality.

Twenty years later I did go back to Vietnam and I got a chance to experience the country and the people from an utterly different perspective. For me it was not any kind of pilgrimage. I just travel a lot. I love Southeast Asia. You can rent a car and share the expenses and have a driver—it’s the best way to see the country.

We went up the coast and met a guy who was a Vietnam veteran. I could tell there was something quite extraordinary about the scene because the guy was sitting there—he had screwed up arms, screwed up legs. He’d hit a mine or something—he was in bad shape. But he was surrounded by these Vietnamese people and it was almost palpable—you could feel the love. It was just coming in on this guy. He had a little kid on his lap; girls were sitting around; old guys there. You could tell they loved this guy. I started talking to him and he said, ‘I got home and I was bitter, angry and for years and years and years I was just pissed off all the time. I’ve come back here and now I’m working on this project where we’re putting solar energy in this hospital in My Lai. And I feel at peace here.’ And he said, ‘Look, I don’t know if it’s doing any good really.’

© Jeffrey Wolin, 'Owen Mike U. S. Marine Corps Lance Corporal Summer 1968-March 1970’, from the series Inconvenient Stories: Vietnam War Veterans

But I thought, ‘Man, I don’t know if you’re making any electricity but you are doing the job; you are binding up the wounds. You’re a hero because I can smell that you are bringing people back together. You replaced hate with love.’

And we talked and talked and talked through the night and finally the thing was breaking up and he said, ‘Where are you going tomorrow?’ And I said, ‘We’re going up north to the DMZ.’ He said, ‘I got one suggestion: Go to My Lai.’

The next day we were driving in the van. There’s really only one good road that goes up the spine of Vietnam. There was a dirt road that teed off and our driver stopped and said, ‘My Lai is down that way about twenty klicks.’ And there were five of us and two said they wanted to go and two said they didn’t want to go and so I was it—I was the deciding vote. I don’t go for old battle sites—I don’t have enough imagination or something so I know I wouldn’t have gone but I respected that fellow’s opinion. So I said, ‘Yeah, let’s go.’

So we drove there and got to the place and we walked in through this arch and the whole area was covered with flowers someone had planted. It was just a field of flowers. And I didn’t even know I had all that sadness in me because I broke down, uncontrollably, just seeing all those flowers. I really didn’t think I needed any resolution but I guess I must have and I was glad for that. And whoever planted those flowers, I salute them, because that’s what you have to do.

© Jeffrey Wolin, ’James Claude Arnold U. S. Navy E-4 July 1966-February 1968’, from the series Inconvenient Stories: Vietnam War Veterans

At one of the museum openings for “Inconvenient Stories”, John asked me if I ever thought of photographing and interviewing “the other side”— Vietnamese Army veterans. But I wondered how I would find Vietnamese veterans. And I didn’t speak Vietnamese. Nevertheless, that conversation planted a seed and started me on what became the sequel: portraits and interviews of Vietnamese veterans.

I began by photographing ARVN (Army of the Republic of Vietnam) veterans here in the US at the suggestion of the Vietnamese American artist, Dinh Le. These were our former allies from South Vietnam who either fled in 1975 when Saigon fell or were sent by the North Vietnamese to “re-education camps” for years before emigrating. Some were “boat people” who fled on overcrowded, barely sea-worthy craft. Sometimes they were attacked by Thai pirates. There are over a million Vietnamese living in America, largely as a consequence of the war.

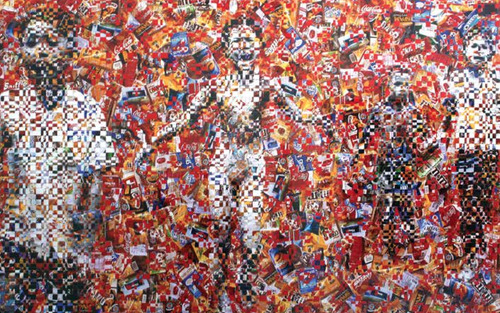

© Dinh Q. Lê, Doi Moi (NapalMeD Girl), 2006

In December 2007, accompanied by John Linnemeier, I visited Vietnam for the first time and had a chance to photograph and interview “the other side”—North Vietnamese Army veterans of the American War (as it is called in Vietnam to distinguish it from the French War, the Japanese War, etc.) The faces I photographed and the stories I heard, not surprisingly, revealed a very different picture of the war than one hears from the American vets.

John Linnemeier and I returned to Vietnam together a year later—this time we stayed in the south, where most battles were fought. I photographed and interviewed North Vietnamese Army veterans, guerrillas, veterans of local militias and civilians whose misfortune it was to be caught in the crossfire. Some witnessed massacres in their villages. But everyone treated us with warmth and curiosity and respect. The NVA veterans loved meeting John and they would show each other the scars from their war wounds, wondering if they were ever in a situation where they shot at each other and then laugh and hug.

© Jeffrey Wolin, 'Ho Phuc Ngon Vietnam People’s Army Lieutenant Colonel’, from the series Vietnam Veterans: Portraits of the Other Sides

I became increasingly interested in the way the lives of the veterans from the opposing armies became intertwined because of the war. The new larger project that emerged, “From All Sides” opened in Lyon, France as part of the Photo Biennale, Lyon Septembre de la Photographie, in 2010. In the gallery, the veterans from the three different armies were interwoven based upon interconnectedness of their stories and/or visual relationships.

© Jeffrey Wolin, 'Nguyen Van Phuoc Civilian near the DMZ in Quang Tri’, from the seriesVietnam Veterans: Portraits of the Other Sides

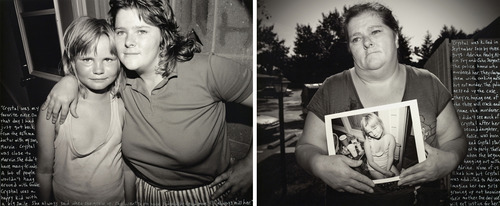

And finally, to end with my current work, several years ago the front page of our local newspaper featured another gruesome murder. A 29-year woman named Crystal Grubb was reported missing and then her body was found in a cornfield just north of town. In that 29-year old face I immediately recognized one of the kids from Pigeon Hill that I had photographed 20 years earlier. I located her mother and gave her the portraits I had made of her daughter as a child. She told me of Crystal’s last days, of her abusive boyfriend who was arrested for cooking meth the night of Crystal’s disappearance. And I realized it was time to revisit Pigeon Hill and see if I could find the people I had photographed a generation earlier to learn how their lives had turned out.

© Jeffery Wolin, 'Crystal with her Aunt Judy, Pigeon Hill / Judy Holding Portrait of Crystal after her Murder, Acadia Court’, 1991/2013), (2013), from the series Pigeon Hill - Then and Now.

Obviously I couldn’t photograph Crystal again, so I had her Aunt Judy hold a portrait of Crystal from two decades earlier and recount the story of Crystal’s murder. It eerily paralleled that of Ellen Marks whose murder had brought me up to the Hill in the first place 25 years earlier. Although I am using a medium format digital camera now, I am endeavoring to match the look of the earlier selenium toned, gelatin silver prints photographs made from negatives. I like a certain level of ambiguity as we look forward and backward in time. It helps raise more questions about the nature of memory.

I had to visit a maximum-security prison to photograph one of the people I had photographed years earlier as a kid. His crime was failure to pay child support. The US has the highest rate of incarceration of any nation on earth. We put people in jail at nearly twice the rate of Russia; seven times that of France. It’s a national disgrace, related to the privatization of prisons and the failed war on drugs.

© Jeffery Wolin, 'Timmy, Pigeon Hill / Timothy, Wabash Valley Correctional Facility’, (1991/2013), (2012) from the series Pigeon Hill - Then and Now

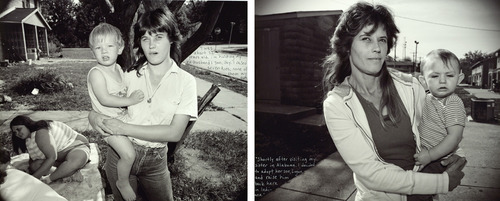

After four years between 1987-1991 and the past four years, “Pigeon Hill: Then and Now” opened at la galerie le Bleu du Ciel in Lyon, France and was shown at Catherine Edelman Gallery in Chicago this past winter (Artist talk video from here) . We paired the then and now images side by side—we also screened a video with interviews we did of eight of the people in the series discussing their own responses to the photographs, past and present. Viewers can draw their own conclusions about the underlying issues of class, poverty, nature/nurture, aging, trauma, memory, etc.

Although these issues are embedded in this series, my main interest is in the faces themselves, especially when juxtaposed with the earlier portraits. One can see the effects of the passing of time and the ways in which life’s experiences (good and bad) are written into these open and expressive faces.

© Jeffery Wolin, 'Tina with Jay, Pigeon Hill / Tina with Logan, Pigeon Hill’, (1988/2013), (2012) from the series Pigeon Hill - Then and Now

Biography

Jeffrey A. Wolin is Ruth N. Halls Professor of Photography and Director of the Center for Integrative Photographic Studies at Indiana University School of Fine Arts, where he served as Director from 1994-2002. He has been awarded two Visual Artist Fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts and a John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation Fellowship for his photographs with text.

His work has been exhibited in over 75 solo and group shows in the US and Europe since 1990 including Houston Museum of Fine Arts; Museum of Contemporary Photography, Chicago; Los Angeles County Museum of Art; Museum of Modern Art, New York; George Eastman House, Rochester; Corcoran Museum, Washington, D.C.; and the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York.

Wolin’s series of portraits of Holocaust survivors, Written in Memory: Portraits of the Holocaust, was published by Chronicle Books, accompanying solo exhibitions at the Art Institute of Chicago; International Center of Photography, New York; Chrysler Museum of Art, Norfolk, VA; Indianapolis Museum of Art and Haus Bill in Zurich, Switzerland. Work from this series was included in Mémoire des Camps, which opened at Hotel de Sully in Paris and traveled to Fotomuseum Winterthur, Switzerland; Palazzo Magnani, Italy; and Museu Nacional d’Art, Barcelona, Spain.

Wolin’s solo exhibition of portraits of Vietnam War Veterans opened at the Museum of Contemporary Photography in Chicago in 2005. Umbrage Editions of New York published an accompanying book, Inconvenient Stories: Vietnam War Veterans. Wolin traveled to Vietnam twice to photograph Vietnamese war veterans and expanded the project to include all sides of the war. From All Sides: Portraits of American and Vietnamese War Veterans premiered at the Photo Biennale, Lyon Septembre de la Photographie in 2010.

Wolin’s work is included in numerous monographs and other books including Swimmers, Aperture, New York; Waterproof, Editions Stemmle, Zurich; An American Century of Photography, Abrams, New York; Searching for Memory, Basic Books, New York; Common Ground, Merrell, London & New York; and Mémoire des Camps, Editions Marval, Paris.

His photographs are in the permanent collections of many museums including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Los Angeles County Museum of Art; San Francisco Museum of Modern Art; Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City; Museum of Contemporary Photography, Chicago; Cleveland Museum of Art; Houston Museum of Fine Arts; Art Institute of Chicago; New York Public Library, New York; International Museum of Photography at George Eastman House, Rochester; Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; Bibliotèque Nationale de France, Paris; and Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Jeffrey A. Wolin is represented by Catherine Edelman Gallery in Chicago.

---

LINKS

Jeffrey Wolin

United States

share this page