© Marc Lathuillière, Studio Tang Daw

Tell us about your approach to photography. How it all started? What are your memories of your first shots?

Marc Lathuillière (ML): There is not much to say about the first pictures I took as a teenager with a camera offered by my grandfather. It turned a bit more serious when I became a travel writer, being frequently sent on assignment with press photographers in France and abroad. That’s how I learned the basics, trying to imitate them with my non professional camera. I thought I was not very good, so I gave up for a while. But in a sense I went on practicing photography without a camera. After all, coupled with our eyes, the brain is the best camera obcsura. Traveling with photographers, I was witnessing how they framed the world, and took part in that construction as I was often assisting them.

The first important shot I remember is witnessing a “wrong” picture being taken. I was with a photographer in Quebec, doing a story at a forest lodge in the winter. To preserve the food, the staff was using ice chainsawed from a nearby frozen lake. The photographer asked one of the guys, dressed like a trapper, to perform the same action with a huge antique hand saw he had seen adorning the reception cabin. I told my friend: “You know very well French Canadians hate to be perceived as backward lumbermen. This is exactly what this picture will tell our readers”. The image of course was published, its caption saying it was the normal way to cut ice in this part of the world.

Witnessing how press and commercial photography was building cultural identities and reinforcing national if not racial stereotypes, I developed a problematic relationship with this practice.

© Marc Lathuillière, Anakot (The Fortune Teller)

How did your research evolve with respect to those early days?

ML: The real start was my stay in Seoul in 2003-2004, where I was working as a journalist for the South Korean radio. Overwhelmed by the culture shock, my creative answer was not verbal. It should have been, since I was still a writer. But no, the real reply to those jingoist clichés aired by my employer was to use the power of images. During a one week vacation, I crossed South Korea on a small 125 cc bike, and developed a photographic game meant to unravel those cultural stereotypes. When I came back to Seoul, I had my first series, called ‘Transkoreana’, which was subsequently published by a Korean house, Noonbit, and shown in the country, in Hong Kong and later in France.

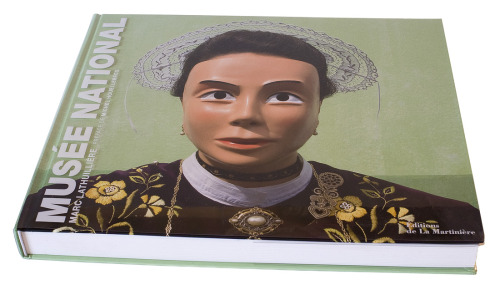

Cultural shifts play a major role in the way I conceive my projects. The next one, ‘Musée national’ (National Museum) stems from the reversed culture shock I experienced when I came back to France in 2004. I had lived in Asian fast movies societies, and found myself back in a country where people cling to their heritage, resisting world changes in order to preserve what they perceive as a “French identity”. I realized we were progressively turning our country into one huge open air museum. To the delight of foreign tourists, of course. Coupled with the invasive use of digital photography, tourism is a truly modern phenomenon that deeply affects societies, and the way they perceive themselves and mutate accordingly. For National Museum, I ask the French I meet around the country to wear an identical mask, and take their portrait in a context relating them to a heritage. Defacing and freezing the subjects, the mask casts these daily surroundings in an estranging light, revealing the stereotypes upon which we build our lives.

© Marc Lathuillière, On the Carlton Beach - Christian Toussaint, Producer, Cannes Film Festival (Alpes-Maritimes). Courtesy Galerie Binôme

Mirroring this long term project, I developed another one called ‘Fluorescent People’ between 2007 and 2010 in Northern Thailand. Working in immersion in a remote village of the Lisu hill tribe, I confronted its inhabitants with strange installations of colorful mass consumption products. I used pink balls, jelly pots or PVC pipes – materials of a fast changing lifestyle – to design a kind of outer space in which they posed in their brightly colored clothing. A critical rereading of ethnical photography, these clichés intent to deconstruct how the genre assigns minorities to a timeless past, a mental frame akin to a reservation.

Can you tell us more about your biggest project, ‘Musée National’, and your collaboration with Michel Houellebecq.

ML: It’s a project I have been working on for the last 11 years. I have taken the masked portrait of more than 500 people in around thirty departments across the country: farmers, politicians, winemakers, fashion designers, village butchers, museum curators and even a few celebrities like Nouvelle vague moviemaker Agnès Varda. I thought it might come to an end when it was published last year: the book, conceived withEditions de La Martinière, contains 160 photographs, and it’s a pretty good synthesis. But in fact its publication was for me a liberation. It took four years to give it birth – an overdue pregnancy, really – and I restrained myself from adding too many portraits to the series. I now feel free to go on taking pictures of regions or cities – like Arles – or functions – like the literary jury, with Frédéric Beigbeder, president of the “Prix de Flore”, wearing the mask – I have not addressed in my typology before.

© Marc Lathuillière, Book ‘Musée National’, Editions de La Martinière

The recognition the series has achieved lately owes much to Michel Houellebecq’s support. We met three years ago, when I got in touch with him for a group show in which, as a curator, I wanted to include three of his photographs; though he is a writer, he has a very intriguing and exciting use of photography. The show never took place (the gallery who commissioned it closed down and I’m still looking for another venue), but preparing it gave us ample occasion to confront our views on France, deindustrialization and tourism. Though many sociologists have already analyzed this process we call “museification”, Michel, in his 2010 novel ‘The Map and the territory’ and myself with ‘National Museum’ are to my knowledge the two only artists or writers who gave this concept so much thought. There are also similarities between some of the works developed by Jed Martin, the fictional artist whose life is told in the novel, and my own. These common grounds led Michel to write a text on National Museum, called ‘A remedy to the exhaustion of being’ (it has just been translated into English). It subsequently became the foreword of my book. Under the supervision of Valérie Fougeirol, one of the three curators of last year’s Month of Photography in Paris, we also join forces in the double exhibition called ‘Le produit France’ (The French Product). While I curated his first large solo show of photographs, ‘Before Landing’, at the Pavillon Carré de Baudouin, he supported mine, ‘Musée national’, at Galerie Binôme with his writing. With the support of Gares & Connexions SNCF, the branch in charge of stations at the French national railways, some of our photographs were also displayed in Paris stations, Gare de Lyon and Gare d’Austerlitz respectively.

© Marc Lathuillière, The Quality Meat - Alain Daire, Butcher, Cunlhat (Puy-de-Dôme). Courtesy Galerie Binôme

About your work now. How would you describe your personal research in general?

ML: One of the main drives is my curiosity for cultural systems: foreign ones and those I originate from. Trying to understand them, I usually come across stereotypes that bend and distort our perception. So you could say I’m a stereotype hunter. I experiment different visual approaches to unravel and deconstruct them, trying out new strategies for each project.

Generally speaking, my main method consists in modifying our usual perception of a photograph through the addition of extra layers of reading. They can be intrusions inside the image itself – a simple mask in ‘National Museum’, or entire installations in ‘The Fluorescent People’ – but also reflection effects in the way I show them. In my most recent body of work, called ‘Dispersions’, some photographs of suburban sceneries – a contemporary cliché - are mounted on mirrors, others projected on a mirror ball. These effects are attempts to dissolve visual boundaries, but also, symbolically, to suggest a critical approach of the influence of political powers on the making of territory photographs.

© Marc Lathuillière, The Sky Fire Tree

What do you think about photography in the era of digital and social networking?

ML: Digital capture and post-treatment make photography one of the most fascinating field of experimentation in contemporary art. It is also shaking up the certainties of old style documentary photography. We knew it before, but now it can’t honestly be denied: what we capture with a camera is not the reality. Just a reality. A framed and static one.

Social networks are also an exciting new field for the artists: they are new extensions to the body in which images play the main role, mixing memories and fictional projections. I actually intend to launch a project using one of the most recent mobile phone networking applications, looking for partners to develop it. New practices in social networking should anyhow be studied and apprehended with a certain degree of distrust. They triggered a rocketing inflation in the use of photographs. And as photography is shaping the world in a distorted way, fostering its commodification, this evolution does also concern me.

Do you have any preferences in terms of cameras, techniques and format?

ML: I usually shoot with a digital reflex camera. The brand is Japanese. 24 x 36 is my preferred format, but I would love to see one of those camera makers develop a professional reflex allowing the use of the 16:9 format: it’s cinematic and close to the human eye.

Is there any contemporary artist or photographer, even if young and emerging, who influenced you in some way?

ML: I am certainly influenced by some of my artist friends, if not by their work at least by their dedication. But as far as the non living ones are concerned, my first visual influence is Quattrocento: when I was studying in London, I would drop by every week at the National Gallery to look at the amazing way Mantegna, Bellini or Botticelli painted skies and perspectives. It is the light of a lost paradise. As I did my first photographer steps in Asia, I was also probably influenced by the colors and playful protocols of contemporary Asian photography, by Kacey Wong (the ‘Drift City’ series) or Manit Sriwanichpoom, to name only the artists I met.

© Kacey Wong, Drift City (Munich, Germany), 2006

Social portraiture is also high in the list of my references, and I have a great respect for August Sander, Arnold Newman, Jeff Wall and Martin Parr. But for their radical and critical approach of photography, Alfredo Jaar and Joan Fontcuberta’s works are for me the truly quintessential ones.

I should also mention that a lot of my sources of inspiration are negative ones: contemporary photography produces its own stereotypes, often showing me the highways I must avoid.

Three books of photography that you recommend?

ML: All the books published by Joan Fontcuberta. The others are more books on photography.

‘La photographie contemporaine’ by Michel Poivert: a very bright and broad approach on today’s photography, but I’m not sure it’s been translated into English. If not, it should definitely be. More of an essay, and mostly focused on some big names of the contemporary scene, ‘Why photography matters as art as never before’ by Michael Fried, develops a theory on the importance of “absorption” in portraiture that is as exciting as it is doubtful, making it really thought-provoking. Writings by Roland Barthes, Rosalind Krauss and French philosopher Clément Rosset have also nurtured me a lot.

Is there any show you’ve seen recently that you find inspiring?

ML: ‘After Eden’, the most extensive exhibition of the Walther Collection ever, is presently shown at the Maison Rouge in Paris: a must see for those who will be here for Paris Photo. More than 800 photographs are displayed – only one part of this major private collection. The dialogue between the German-American collector, Artur Walther, highly serial and conceptual, and African curator Simon Njami, more focused on cultural studies, makes it very rich in meanings and highly inspirational.

© La Maison Rouge, Après Eden / La Collection Walther

Projects that you are working on now and plans for the future?

ML: I am presently planning a Tour de France of the Musée national exhibition. Almost like a political campaign – the next presidential election in France is only 18 months away – it will tour different museums, festivals and art venues in the coming two or three years. One of the main shows, in 2017, will be at the Creux de l’enfer, an impressive art center set in a former industrial site in Thiers, followed by a participation in a retrospective on French territory photography at the BNF (Bibliothèque National de France), which has recently acquired Musée national prints. There might also be a stage of this tour on the English soil, at the Guernsey Photography Festival, and possibly in Victor Hugo’s exile house there. It seems there is a rising interest for Musée national abroad, not only in Europe, and exhibitions in Asia are also in the pipes.

© Marc Lathuillière, Somehow Anyhow: The Towers, Duraclear on mirror, 2013

I am also developing my last body of works, the ‘Dispersions’, a reflection on image and territories, including photographies mounted on mirrors as well as cultures of commensal bacteria. It is based on an essay I am presently writing, called ‘Territorism’.

How do you see the future of photography in general evolve?

ML: I feel the deconstruction process that has impacted photojournalism will also affect documentary photography. A lot of young artist are already playing with the limits of photography, in a multimedia way, blurring the limits with video, installation and even painting. Some approaches are highly technological: using screens or monitors, they indicate a dematerialization of the medium as a long-term tendency. Others show a come back to old printing techniques, like cyanotype or daguerreotype. I just hope this renewed interest will not give birth to a new formalism, like the one that developed in the French painting with the “Supports-Surfaces” movement in the 70’s. If photography is reaching its “Film/Surface” age, as I think it does, artist should not forget that playing with its forms is much more stimulating and involving when the subject addressed is the world outside the dark room: our complex and suffering contemporary world.

---

LINKS

Marc Lathuillière

Galerie Binôme

share this page