Roland Barthes said that the photographed object is always deceptively natural. In this sense, your series Skeletons in the Closet is enlightening, as the illusion is made explicit from the choice of the object represented. Tell us how the idea took shape in this project.

Klaus Pichler (KP): You are right, the series is indeed a meeting of two things that are deceptively natural - photography as a medium and the natural history museum as an exhibition place of an amount of staged realities. But let me explain it from the beginning. As I wrote in the project statement, it all started by chance, when I happened to catch a glimpse through a basement window of the museum of natural history one night: an office with a desk, a computer, shelves and a stuffed antelope. This experience left me wondering: what does a museum look like behind the scenes?

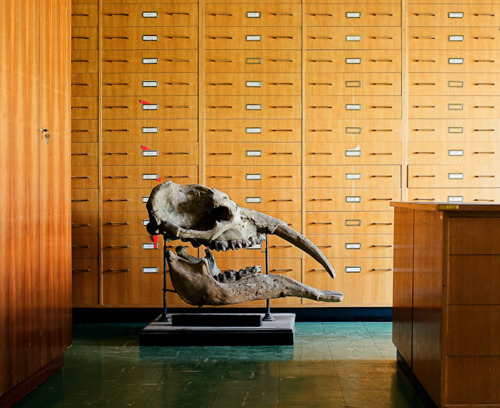

In the beginning my main interest was to find out more about the look of the ‘backstage area’ of the museum - the basements, depots and storage rooms. When I firstly visited some of the dozens of storage facilities, I noticed that there were plenty of stored exhibits, strangely interacting with each other or with the surrounding spaces - basically the same like in the exhibition spaces, but totally different, too.

This similarity and difference at the same time felt like something I had to go more into the deep, and the following research lead me to the 'diorama’, invented by Louis Daguerre (also known as the inventor of photography with his famous 'daguerreotypes’) in the 19th century. A 'diorama’ is a three-dimensional model of an idealized landscape, in context of a natural history museum mostly life-size, where taxidermied animals are staged in their simulated natural habitat in front of a dramatic backdrop painting. The aim of a diorama is to create a conception of nature to illustrate the natural habitat of the animals. This entity of a diorama was the clue for the 'Skeletons’- series, because I found a concept with an origin in the exhibition that also had validity in the backstage areas. If you bring this concept forward to the backstage of the museum, you find dioramas too, but with a totally different look and a totally different way of genesis.

© Klaus Pichler from the series 'Skeletons in the Closet'

The center of the backstage diorama is the exhibit, being in interaction with other exhibits or with the surrounding room - and in contrast to the exhibition spaces these dioramas didn’t get staged consciously, but by chance. They didn’t get staged by curators, they staged themselves (of course with the 'help’ of the scientific personnel of the museum) out of different reasons, mostly because of the principles of storage in a limited space, and also because of the scientific systematic they are archived after. These pragmatic necessities in combination with the exhibits placed in front of the bare walls of the storage rooms sometimes lead to bizarre scenes. I considered these scenes as still lives, perfectly fitting for photographic images. My main task was to search and find these still lives to transfer them into photographic pictures. I did not stage anything, I was just searching for scenes that fit into the concept of a diorama - and I found plenty of them. In connection to the question, the interesting aspect about these bizarre scenes of the series is that they directly link to photography as a medium - and vice versa the pictures also have their analogon in reality. Both, photography itself and a natural history museum are deceptively natural. And both are like a split second taken out of real life: the lifelike animals, taxidermied in lifelike moves, not being able to make a different move than the pose they are taxidermied. If you look at the picture of the archaeopteryx trying to catch the firefly, one thing is clear: the firefly never ever will get caught by the archaeopteryx in reality, neither will it get caught in the picture.

© Klaus Pichler from the series 'Skeletons in the Closet'

Dealing with this particular series (Skeletons in the Closet) is somewhat a painful experience, like being faced with a clear and merciless representation of an idea of death. We may also consider it a metaphor for the implicit meaning of photography, for the trauma each time renewed of representing what no longer exist, and therefore of being in a perpetual contact with it. How much of this is deliberately induced and what is rather left to the free creative act of the spectator?

KP: If you look at the basic concept of a natural history museum - presenting dead animals in their staged and artificially natural surroundings, it somehow seems macabre. But if you walk around in a natural history museum, you will notice one thing: the visitors are mainly families with kids, strolling between the dead animals with pleasure. This on the one hand reveals the strange and surreal character of a natural history museum, and on the other hand shows how the idea of death gets pushed away in our society. If you see it in a provocative way, the taxidermied animals have transcended the state of a living or a dead creature - the have reached a new form, status and type by being taxidermied, they are neither dead nor alive, they are some kind lifelike statues now. Photography itself often has the meaning of a medium of remembrance, especially if it comes to photos of people that have passed away. Photography indeed is a renewal of the trauma of loss every time you watch a photo of a dearly missed person, but on the other hand it also helps to keep the memory alive.

In connection with this series, there is a second layer of background information that is linked to the provenience of the exhibits: the story of a natural history museum, at the time they were created (mostly in the 18th century), is a story of colonialism, of exploitation and racist connoted exposition. The grounding of these museums always had its basis in the distinction from the ‘savage’ and in the lust for ‘exotic’ animals and objects from ‘savage’ tribes. So there is a lot of blood sticking on the older exhibits. I had that in mind from the very beginning, and when I found the bizarre and somehow humorous still lives in the storage rooms I realized that I will be able to create an assumedly ‘easy’ and funny series with this really dark background. I tried to use these facts to create a somehow contradictive and controversial approach to evoke the viewers sensitivity and interest in the history of these museums. I realized, when the ‘Skeletons in the Closet’- series was exhibited, that this dual concept totally works: the viewers entered the gallery, being amused and delighted by the pictures. Later, when I told some of them about the history of the museum, the ways of how the exhibits got into the museum at that time and the colonialist/ racist practices behind that, they started to look at the pictures again, this time with a different point of view and much more careful. So, to answer your question, it was my intention to create a series that assumedly is a ‘funny’ project, but makes a 180 degree turn in meaning if you get to know the historical background of the museum. And therefore, also to deconstruct the first view, to depict that there is a second meaning behind the story that reframes the whole outcome of the photos.

© Klaus Pichler from the series 'Skeletons in the Closet'

The garden, the Hortus conclusus, has in itself the meaning of a place enclosed, isolated, and somewhat artificial and self-reported. In your series Middle Class Utopia, beyond the economic and social issues that this project highlights, the garden itself is almost a mirror of the senseless struggle undertaken by men to defend themselves against the threats of the outside world, with results often grotesque. Do you think that the human need to build a place in one’s own image and likeness, a place to own and to be named, is always in contrast with being part of the world and nature?

KP: In general I don’t think so, because, as you already mentioned, it is a fundamental need of beings, no matter if humans or animals, to inhabit a place and to call it one’s own. And, linked to that, to design it in a certain amount. This doesn’t necessarily mean an escape from everything outside the boundaries of one’s private space. In the case of the garden colonies (called ‘Schrebergarten’, named after their inventor Moritz Schreber, 1808- 1861) portrayed in the Middle Class Utopia - series, the absence of the outside world definitely is stronger. The example of these colonies for sure is an extreme one, since life in these colonies is synonymous with an escapist concept of living - there even is a phrase in german language called 'Schrebergartenmentalität’ (Schrebergarten mentality) which describes a narrow-minded, disinterested and ignorant approach towards the rest of the world. The isolationist life in the garden colonies is, to a certain amount, definitely self-chosen - the inhabitants of the gardens describe it as a big advantage to live in the middle of a city without being annoyed by urban life. And they don’t want to get disturbed in their idyls, neither by people from the outside nor by vermin and, most of all, not by burglars. Nature itself is friend and foe for them at the same time: one the one hand they enjoy living in an idyl with bushes, trees, flowers and trimmed lawn. On the other hand the growth of every plant is declared as enemy that has to be fought with the help of trimmers, lawnmowers, scissors and saws. This leads to a grotesque and sometimes mannerist look of the gardens, consisting of green elements in a perfect shape.

© Klaus Pichler from the series 'Middle Class Utopia'

The self-chosen isolation in the garden colonies is also manifested by different levels of barriers - one boundary outside these colonies which gives them the character of a 'gated community’, and one around every single garden, most of them in more layers (hedge, matting, chain-link fence). If you wander around in the paths between the gardens on a warm day, probably a Sunday, you don’t see any people, but you hear them talking behind the hedges and you can be sure that you are being watched. And, as a strange but somehow understandable fact, these strict barriers to the outside lead to a different transition between the house and the garden: in the colonies, the garden is seen (and designed) like an outdoor living room. And, as one aspect of that, the garden is also used in a very private way and treated like an indoor room, especially when it comes to cleaning and care. When I was wandering through the colonies, I imagined it like an indoor living room where you have to cut and trim the cupboards and the sofa twice a year - a grotesque picture…

© Klaus Pichler from the series 'Middle Class Utopia'

I want to clarify one thing: the persons depicted on the photos of the series definitely are the nicer and more open-minded ones of the colonies. They showed interest in my work, shared their (sometimes quite paranoid) thoughts about life in the colonies with me and agreed to take part in the series. The less nice ones of course refused to get photographed and weren’t too happy about an intruder with a camera who disturbed the idyl…

© Klaus Pichler from the series 'Middle Class Utopia'

All your work has the flavor and the force of a revelation. Jean-Paul Sartre said that the function of the writer is to ensure that no one can ignore the world or feel innocent about it, thereby covering the role of a “troubled conscience”. Similarly, can we affirm that the photographer’s choice is to unveil the world and, in particular man to other men, so that they take in front of the subject exposed all their responsibility?

KP: This is definitely correct, especially when it comes to the role in photography as a tool of information. I strongly agree that it is necessary to use photography as a visual power to depict everything that is an issue, including political, social, cultural, religious etc. topics. In our society of media and information, especially since the mass usage of internet, photography became more important than ever. And in my opinion it is necessary to be conscious that photography is a medium that, combined with media, has the power to end wars, to spread information, and by that, to improve critical situations. I have deep respect for every photojournalist who risks his life in documenting wars and conflicts, and I think it is a necessity to document every critical situation around the world.

I for myself couldn’t do the work of a photojournalist because, although I understand the aim and necessity of every graphic image taken in a war, my personal mission in taking photos ends where people get depicted who are under pressure or can’t do anything against being photographed. I work differently, I try to work with the cooperation and support of my ‘models’ and to create something together with them. I see my portrait series as a sequence of short-time-cooperations with different random people who are involved in the creative process. No matter if this leads to staged or spontaneous pictures. According to that, my topics are different and I try to find a different way of taking the viewers into responsibility. I don’t necessarily try to change anything with my pictures, but to depict a situation/issue/social group and to appeal to the viewer’s intelligence and fantasy to reflect about the pictures. And, in best cause, to activate an own creative process in their mind.

© Klaus Pichler from the series 'Middle Class Utopia'

---

LINKS

Klaus Pichler

Austria

share this page