Tell us about your approach to photography. How it all started? What are your memories of your first shots?

Kerim Aytak (KA): I first started taking pictures as a hobby alongside my early forays into film making. My parents were antique dealers so we travelled a lot by car, and taking photographs would be the thing that I did while they went round fairs. It then evolved into a more serious pursuit until I realised, finally, that I wanted to make photographs more than I wanted to make films. Photography is a means by which to actively engage with the world around you so long as, obviously, you resist the obvious.

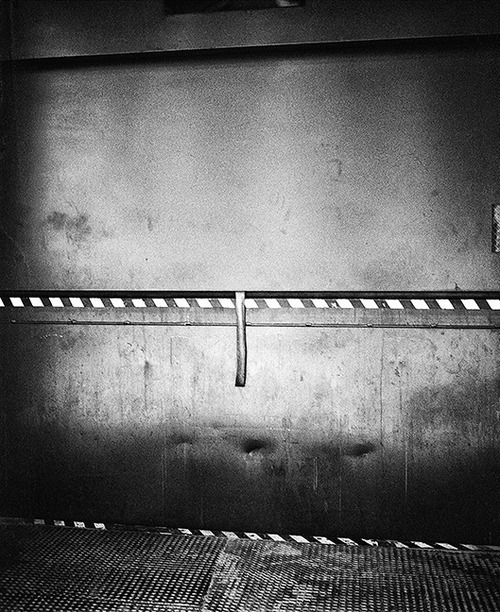

© Kerim Aytac

How did your research evolve with respect to those early days?

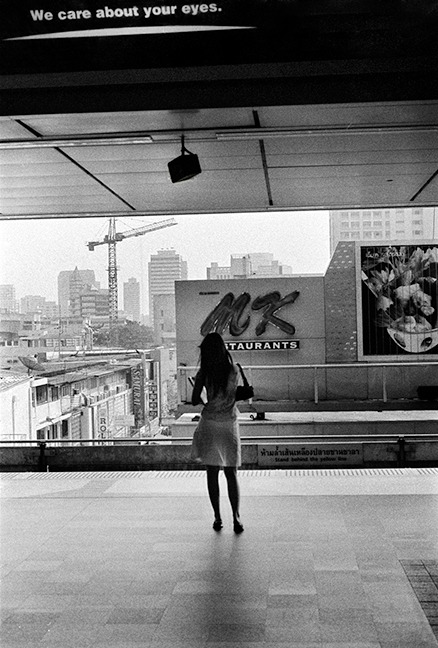

KA: Due to the fact I was born in Turkey and grew up in London, I was initially caught up in a stylistic impasse. Turkey is all ‘decisive moment’; there are a million pictures to take everywhere you go. Istanbul in particular is that kind of place, with life lived on the outside and on display. London, on the other hand, is internal, a place where people hide themselves away and avoid eye contact. My first projects in Turkey were therefore classic ‘Street Photography’, seeking out the coincidences of public life, but as I began to make work in the U.K I developed an interest in the idea of absence. I realised that I preferred to take picture of people after they had been there, in absentia. This also appeals to my graphic sensibilities, allowing me to make compositions unencumbered by the need to allow for the presence of a figure. I guess I began to find the classic ethos that still defines Street Photography (people in decisive moments) as limiting and strangely dictatorial; I wasn’t free to really take the pictures I wanted to that way. The urban landscape isn’t simply defined by the fact people who use it. It exists itself, living and breathing independently.

© Kerim Aytac

Tell us about your educational path. BA in Media and Communications and MA in Image and Communications. What are your best memories of your studies? What were the courses that you were passionate about and which have remained meaningful for you. Any professor or teacher that has allowed you to better understand your work?

KA: I did both my degrees at Goldsmiths University. My degree was in Communications but I focussed mainly on Film Studies and Film production. I was also trying to work in Film at the time. Although I very much enjoyed the theoretical aspects of the course, I found the practical work stifling. The emphasis was on commercial work in preparations for a potential career in the industry and wasn’t very creative therefore. By the end of the course, I felt very proud of what I had achieved technically but hadn’t made any progress artistically. I had also come to realise that the main reason I wanted to make the films was so that I could shoot them more than anything else and that I had no real desire, or desire enough, to make the compromises necessary in the film-making process. The course was great but it helped to realise that my future lay in a more artistic field. It was for this reason that the M.A in Image and Communications was such an important and positive experience for me.

© Kerim Aytac

The Image and Communications M.A at Goldsmiths was set up by Nigel Perkins as a kind of rescue action for people in positions like the one I was in. The cohort was mainly talented artists who hadn’t, for whatever reason, had the space to develop themselves. It was a second chance for those seeking to develop their creative potential. Output was mainly photographic but there was video and interactive work also. What really distinguished this course from others was a really light touch approach to project work and much stronger emphasis on creative exploration that didn’t need to be justified critically or historically. We were encouraged to follow paths that may not have resulted in original work per se, but were instrumental in developing our practice. I loved every minute of it and believe, truly, that I would not be an artist today had I not attended. At that time, Ian Jeffrey, noted Photographic historian and writer, was a tutor on the course and was very influential on my practice. He was very encouraging and turned me onto Japanese photographers like Moriyama and Tomatsu, both of whom are big heroes of mine. He also helped me to think of my work as part of universal collaboration in which all artists help and feed off each other.

© Kerim Aytac

What do you think about teaching methodology in the era of digital and social networking?

KA: I think that in the age of digital some educational instituations no longer feel the need to teach anologue techniques or provide students with film equipment. This is perhaps a rational approach, but seems a shame when most digital cameras operate by principles established in the pre-digital era which are more readily understood by using film equipment. Another consequence of the use of digital on photography courses is too many pictures. There is a tendency to produce volumes of images rather then exercise any selection at the taking of the picture stage, and then select after. This may well be where photography is heading in the age of super hi res and the Lytro, but encourages passivity when taking pictures. To be a good photographer you need to have developed an individual style, a singular way of seeing which one cannot develop in post-prodcution alone. No image, no matter how big, can compensate for a photographers’ eye.

© Kerim Aytac

About your work now. How would you described your personal research in general?

KA: I would now describe myself as an abstract street photographer with conceptual leanings. My subject matter tends to be the urban or matters relating and matters relating to it, and my style more or less modernist in terms of its graphic qualities. Until now I have shot black and white exclusively as it compliments my style, but am about to embark upon some colour work. I remain pre-occupied with notions of absence and traces. In my most recent project I explore the British New Towns built in the post-war period and try to examine the ways in which a space once designed to represent the essence of what was new, a modernist dream, has itself grown old and decrepit, wounded and elderly.

Do you have any preferences in terms of cameras and format?

KA: I shoot with a Mamiya 7 which produced Medium Format 6x7 frames.

© Kerim Aytac

As I can see you got the chance to exhibit your work in many shows. Any particular advice for young photographers aspiring to display and exhibit their work without drowning in the ocean of images in which we daily swim?

KA: Although I am by no means established, my main advice for young photographers would be to find a way of surviving and lasting. Most photography graduates are bursting at the seams when they graduate but have burnt out and all but given up 3 years later. It is a marathon and not a race, and if you can find a way of maintaining your practice over a ten to twenty year period, you will eventually succeed and get exhibited. Give up on on the idea of making any money form your work and get a job that allows you the time to make work no matter what.

© Kerim Aytac

Do portfolio reviews at photography festivals. Though these are expensive, they provide invaluable feedback and, eventually, opportunities. Keep sending stuff to people but do not pay to enter competitions you are unlikely to win unless the judges are people you would want to see your work.

Projects that you are working on now and plans for the future?

KA: I’m working on a couple of ideas but it is too soon to talk about them!

© Kerim Aytac

Finally, are there any influences in terms of artists, authors, texts, films, etc. that you’d like to cite as having had a particular impact on how you think about your work or your practice?

© Kerim Aytac

My photographic heroes are Daido Moriyama and Mario Giacomelli. My filmic heroes are Jim Jarmusch and Emir Kusturica.

---

LINKS

Kerim Aytac

England

share this page