Joni Sternbach received her B.F.A. from School of Visual Arts and her M.A. from the New York University/International Center of Photography graduate program. Her work is represented in many significant collections including the Museum of Photographic Arts in San Diego; Maison Européenne de la Photographie, Paris, France; The Cleveland Museum of Arts; St. Louis Art Museum; the International Center of Photography; and the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas, Austin. She has taught her own wet-plate workshops throughout the U.S. and has also been a visiting artist at International Center of Photography, Center for Alternative Photography, Utah State University’s Caine College of the Arts, and the Silver Eye Center for Photography.

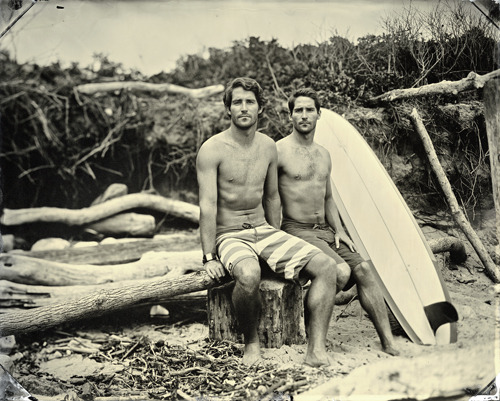

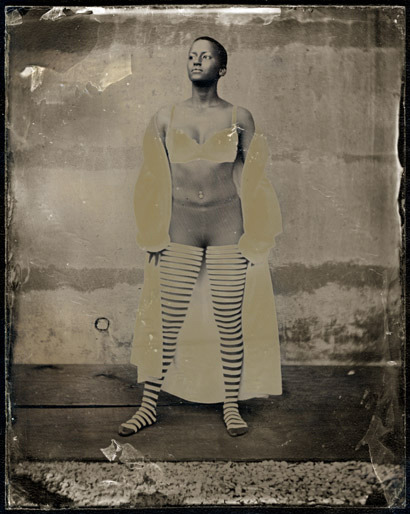

Sternbach is best known for Surfland, an extended body of tintype portraits of surfers. These images have been exhibited at Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, Massachusetts, Blue Sky Gallery in Portland, Oregon, and most recently at the Southeast Museum of Photography in Daytona Beach, Florida. A selection of the work was also published as a monograph in 2009. She is currently exhibiting an updated version of this work, Surfland, Revisited 2006-2011, at Rick Wester Fine Art in New York City.

© Joni Sternbach by Nandita Raman

You’ve taught in both traditional departments and workshop environments. Clearly these are very different experiences. I’m curious to hear some of the pros and cons of both. What was your own photography education like – where did you study and with whom?

Joni Sternbach (JS): I studied photography initially as a fine arts major at the School of Visual Arts and later as a photography major, till I eventually graduated with a BFA in photography. I went on to get a Masters at NYU/ICP and started teaching immediately after graduating. I think that there is a strong continuity and relationship with one’s students when teaching in an academic institution that just does not carry over to the workshop setting. Alternatively, the people who study in a workshop environment are there specifically to study the course you are teaching, so the intention is sometimes different and stronger. My workshops are typically only a couple of days, so that means I get to know my students only so much. As an undergrad I studied with Julio Mitchel and Sid Kaplan, photographing the New York City street scene with a Leica. At the time I was very attracted to reportage photography. By the time I went to grad school in my early 30s, post modernism was in full bloom. I loved the challenging nature of the movement and the idea of creating a photograph rather than going out on the street and finding it. I studied with Sarah Charlesworth, Abigail Solomon-Godeau and Christopher Phillips.

© Joni Sternbach from the series 'Surfland'

What did you learn about teaching from your own teachers?

JS: Be kind…Some critiques were brutal and I am not really sure what anyone learns from that kind of negative experience. As a teacher, I am more interested in giving my students the tools they need to create the work that resides in their imagination. I am less concerned with evaluating whether or not they are great artists, that’s their business. There seems to be some directive in art school about sussing out the imposters.

Many photographers work in black-and-white and color. You do as well, in addition to what has become your signature medium of wet-plate collodion. How do you make the decision – as with your Great Salt Lake series – to work in one medium or another, or even more than one on a particular project? I would also include in this question your work on the seascapes, which appear to be in platinum-palladium as well as gelatin silver in different scales. Can you discuss that work and why you chose different mediums for the final output?

JS: That’s a great question! For me, the concept of the work is what determines the medium. Yet sometimes flexibility is called for. When I went to Utah to shoot, I had my concept and my plan all arranged. I ordered wet-plate chemistry and had that along with other items shipped in. I mixed my chemicals there, made a darkbox and put my kit together only to be completely blown away (no pun intended) by the harsh winds and weather conditions. Fortunately, I also brought along a film back for my 8x10 camera and when it was too windy and/or cold to shoot wet plate I opted for film. So the diversity of the series was determined by weather. It wasn’t my original intention to shoot film there, but I am glad I did. When I first started shooting large format landscape photographs in 1999, I was interested in a very tactile, handmade and beautiful print to accompany this idea. Platinum/Palladium came to mind as I had worked with the medium before and loved the way the metals bonded with the paper to create this everlasting warm-toned print. However, one only gets a print as large as the negative because it’s a contact print process. While I loved the idea of coming up close to the ocean in this small intimate print, I felt it also called for a variant, so I made the decision to enlarge some of the photographs [using the gelatin-silver process] as well. I exhibited them both side by side. I think it’s safe to say that I work with an idea and then find a camera and process that accompanies that idea to best suit the project.

© Joni Sternbach from the series 'Surfland'

When did you begin working in the collodion process and what got you started? I know you studied with John Coffer at Camp Tintype. Was that your first experience with the process? What got you interested in it and what was your experience at John’s place? How was he as a teacher?

JS: My first experience with wet plate was in the summer of 1999 in a workshop with John Coffer. It was a wonderful experience. John not only introduces you to the process, but also to the lifestyle, and more specifically, his. Wet plate is a slow process and John takes his time explaining it; he showed us books and copies of the Collodion Journal while we sat on his porch watching the chickens roam around his land in upstate New York. There were just three of us there so we got to shoot a lot of plates. [We’d] sit and chat around the fire while japanning tin. We also made albumen prints. After the weekend at John’s I was hooked. As a young college student I learned to spin my own wool, weave my own cloth, and sew my own clothes. I liked the idea of making something from scratch and not having to rely on a manufacturer for my basic needs. Wet plate is exactly that. You make your own film from scratch.

© Joni Sternbach from the series 'Surfland'

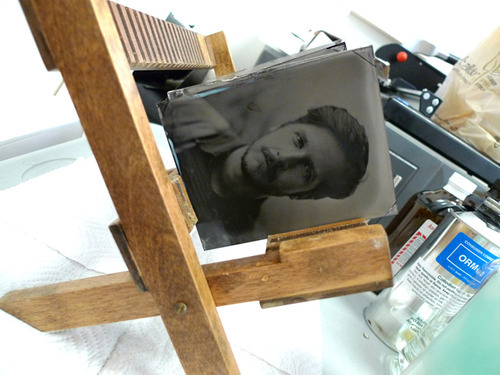

What kind of camera is necessary for wet-plate collodion? How difficult is it for someone to learn the process on their own?

JS: I use a standard 8x10 view camera (Deardorff) with an adapted wet plate back. When I began shooting very few people were making wet plate backs for cameras so choices were slim. Things have changed now that so many people are interested in the medium. There is now is someone in Portland, OR who makes a wet plate holder that fits in the standard back of any view camera.

Wet plate is a little overwhelming at first; there is a lot of information and if your chemical knowledge is limited it can be intimidating. It took me a few years after learning the process to get all the gear necessary to shoot and even longer to take my show on the road. So, I would sum it up to say that it’s not really hard, but it’s complex and takes time.

© Joni Sternbach from the series 'Surfland'

Are there other historical processes that interest you? Do you ever work with wet-plate collodion negatives?

JS: I’ve worked with several historical print processes, but the draw to wet plate was that I could make my own film. I have made many wet plate glass negatives and have a print portfolio from the ‘Abandoned’ series (my first body of work with wet plate). My decision to shoot tintypes (as opposed to negatives) of surfers really stemmed from the limitations of the medium. To shoot a negative would require double the exposure time of a positive and my exposures were already challengingly long.

© Joni Sternbach from the series 'The Salt Effect'

How do you begin teaching your process in workshops? How difficult is it to learn in a short time?

JS: Wet plate is actually very easy to learn but there are many steps involved. My workshop begins with my reading a quote from Alan Greene’s book, Primitive Photography: A Guide to Making Cameras, Lenses, and Calotypes, which says, “I was more and more convinced that instead of evolving in recent years, photography had instead been devolving, due to the pressure of outside economic forces. First there was the industry wide preference for the 35mm camera over large-format, irrespective of the fact that the latter offered more technical and perspective control. Then there was the introduction of the auto-focus cameras. This was followed by the production of tabular-grain films and multi contrast papers in tandem with the phasing-out of slower conventional films and graded papers. Given these occurrences, the movement towards digital imaging seemed little more than the crowning achievement of downward trends. More than ever before, I realized how completely at the mercy of market-driven forces fine-art photographers really were. I resolved that should that day ever come that manufacturers stopped making what I had always taken for granted-namely photographic film and paper-I would already know how to make photographs from scratch.” It’s pretty easy to understand why in this digital age wet plate has had such a resurgence and popularity. I begin my course with a short history of the medium, why I feel it’s valid in today’s changing photographic climate, and explain and demonstrate each step. There is a lot of information, so grasping the concepts quickly is challenging. For me, it took repeating the steps many times till I understood the tools, the pace, and what the results would be.

© Student image Duane

Are there essential concepts or qualities of photography that students are more likely to learn using the collodion process? If so, what are they?

JS: There are many concepts to this chemical process, one of the first is understanding the color sensitivity of collodion, which is insensitive to yellow and ultra sensitive to blue. In the first issue of the Collodion Journal, France Scully and Mark Osterman show color and collodion photographs of a cornucopia side by side, illustrating how the colors of each fruit and flower are translated using collodion. Will Dunniway, another practitioner from California, has a similar image of calico fabrics in both color and collodion, which I use as a teaching tool and in my artist talks.

© Student image Chris George

Do you miss working with students over a longer period of time in doing the workshop circuit? What are the essential differences in the students who take workshops such as yours and those who choose full-time programs?

JS: Hah! I just read this question now, but seem to have answered it in the beginning. One of the benefits to teaching workshops is travelling to other cities and working with a wide variety of people. As far as I know there is only one full time degree program that teaches collodion, however I expect there may be more. In January, I was a visiting artist at the Caine College of Art at Utah State University, where I taught a large group of students the basics of the medium. That was one of the more rewarding workshops because these students have professors who know something about the medium and can support their continuing work. Also, because they are in a full time program, they can really devote themselves to making a body of work in this process, which they have done. And their pictures are interesting.

© Student image Shannon

© Student image Joe by Alissa

© Student image Andy French

What is your outlook now on the traditional handmade photograph in this age of the digital image?

JS: I have always loved handmade objects. It’s part of what attracted me to wet plate and historic hand applied emulsions like platinum/palladium. For me the biggest problem with a digital result is that it I just do not see many beautiful prints like I once did [with photographs] that were shot on film. However, now I have noticed a plethora of alternative-process imagery, especially on the internet, that seems incredibly redundant. Wet plate has a generic quality to it and I find that most people’s work looks alike. Creating a distinctive vision with the medium seems to be very challenging.

You just completed a residency at UCross. Can you tell me more about what brought you there and what you were working on?

JS: I have been working on a series of western landscapes since 2008. My interest in attending Ucross’s program was to visit Wyoming and photograph there. This time I decided to shoot just 4x5 film. I’ve been exploring the western landscape for a while and in that process trying to understand what exactly a western landscape really is. Is it just a photograph made in the west, a song sung to me by my father when I was a kid or is it the culture and history created by imagery in westerns. It’s both myth and mystery to me. While driving on I90 West I noticed a billboard for Buffalo, WY, telling me to “Get Western.” I decided that it was a great title for this work I’d begun, especially since that’s just what I was doing, getting western!

---

LINKS

Joni Sternbach

United States

share this page