This issue focuses on two long-time faculty members in the photography program at Illinois State University in Normal, Illinois. The responses that follow from Jin Lee and Bill O’Donnell offer the reader a glimpse into the dynamics of this particular department and how working together, and in the midwest, impacts their practice and teaching. Fellow faculty member, Rhondal McKinney, who began teaching at ISU in 1983 and founded the Rural Documentary Collection, retired in June. Though absent from this interview, his voice was and remains an important presence.

Jin Lee has been photographing the Midwestern landscapes for the past ten years to explore particularities of a place. Her photographs are included in the permanent collections at the Art Institute of Chicago, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Madison Art Center, and Museum of Contemporary Photography. She has received a 2005 Guggenheim Foundation Fellowship in photography, and is represented by devening projects + editions in Chicago.

Bill O’Donnell earned his MFA from The School of The Art Institute of Chicago and taught at Loyola University Chicago and the School of the Art Institute before joining the faculty of Illinois State University in 2001 where he is an Associate Professor in Photography. The National Endowment for the Arts has recognized his work with a Regional Fellowship, and the Illinois Arts Council has awarded him two Artists Fellowships. Solo exhibitions include shows at the historic Water Tower Gallery in Chicago, the Chicago Cultural Center and Soho Photo Gallery in New York. His work is included in various collections, including the Midwest Photographers Project Collection at the Museum of Contemporary Photography in Chicago, The Chicago Project at the Catherine Edelman Gallery, The Seattle Portable Works Collection and the NEA Visual Artists Fellowship Archive.

© (Left) Jin Lee, Weed 6 (Right) Bill O’Donnell, Window Box

I often feel a bit unnerved as I am the only faculty member who teaches photography at my school, making me the sole voice or somehow the authority on the topic(s). You both have the benefit of sharing the responsibility for the photography area at ISU. Can you comment on how your group dynamic might influence your teaching, the experience of the students and perhaps your own work?

Bill O'Donnell (BO): When I’m working with a student in an advanced level course (anything past Photo 1), I’m always aware of the rich possibilities inherent in the student’s having first studied with Jin or Rhondal. Now, they’re being exposed to a different perspective (my own) and they’ll have to negotiate the coexistence of accord and discord discovered in comparisons of my approach and that of Jin or Rhondal. When in group critique, perhaps with a BFA candidate or one of our grad students, I think it is that much more useful, confusing, irritating, enlightening…for a student to witness instances of agreement and disagreement coming from three faculty members. The student is left with no choice but to weigh those comments and suggestions that are agreed upon, others that wholly contradict each other, and make some careful assessment of their own (the student’s) original intentions and the evident impact of the resulting work. I’ll add here, there have often been instances, during such a critique, when I’ve been so intently focused on the imperative of efficient communication of ideas in the work, that Jin or Rhondal will floor me with a simple, eloquent comment on the exquisitely compelling nature of some delicate play of light or poignant feel for composition. My hope is that the student is attending to both concerns and all the subtle variations in between.

Jin Lee (JL): Over the years, Bill, Rhondal and I have moved our offices in the art building and ended up in the same corridor on the 2nd floor, right next to one another, where we have our weekly spontaneous chats about everything from what the students doing to books we are reading. I think this speaks to the closeness and mutual respect among the photo faculty, which allow us to appreciate our differences in our teaching and in our work, although our values and goals align quite perfectly.

© Jin Lee, Great Water 15

Having worked closely with both of you for three years during graduate school, and in the years that have followed, I’ve gained something different from each of you. I wonder if you can comment on your experience with students in terms of how you feel you’ve impacted their practice or development and/or how you feel about the role of instructor influence in general?

BO: Well, I may as well start with the obvious… I do not want the result of my teaching to be a room full of younger people making pictures like my own. I think we “…impact… their practice…” by walking with them through the odd terrain between their own ideas and a resolution in artwork that is at the very least some semblance of what they felt. We engage in that walk, according to our particular temperament, by adopting the student’s idea as though it were our own. So, now, how might one best manifest this idea? Here’s where things get tricky, because I don’t want the student to arrive at the solution that would have been mine; I want to flit around the periphery of their conscious and unconscious analysis of the problem, nudging here, deflecting there, encouraging when they are achieving a delicate balance of personal expression and intelligible communication with the nameless, faceless viewer.

© Bill O’Donnell, Radio Nook

BO (continued): In my experience, every student, especially a Photo 1 student, is surprised to discover how distinctly particular their vision is and how readily that vision is communicated via the seemingly cold, objective recording device that is the camera. I emphasize the uniqueness of their vision in suggesting that no one else in the room full of students would/could photograph what it was that interested this student in exactly the same way; at least as importantly, it’s fairly unlikely that a good percentage of the others would even have been moved to photograph that subject matter!

JL: One of the most valuable things that I got from my first photo teacher Wendy MacNeil and the subsequent professors is the sense of their total commitment to their work. Being around them, inside and outside the classroom, I was seeing and learning how they reconciled and balanced their art practice with the practice of teaching and living. I am very thankful for all they have shared, and I hope our teaching can have a lasting impact on our students beyond their time at the university.

© Jin Lee, Ground 2

You have pretty disparate backgrounds and your work, while addressing similar concerns in many ways, is also wonderfully distinct. Can you briefly discuss any particular influences in terms of other photographers, artists, writers, musicians, etc.?

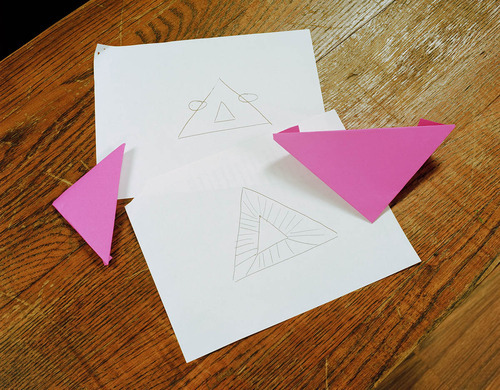

BO: My earliest memories of photographs that were directly inspirational to me are those of Edward Weston and Ken Josephson. I knew immediately on seeing Weston’s work, that I too wanted to elevate the mundane to the wondrous and I knew when I was first introduced to Ken’s work, at about the same time, that I too was interested in making work that wryly and slyly referred to and gloried in the oddities of the medium itself. Later, some of the images that influenced my thinking about picture-making were those of Robert Cumming, John Pfahl, Zeke Berman and Ruth Thorne-Thompson (among many, many others).

The one painter whose work most interested me for many years was that of Gregory Gillespie. I certainly looked at a lot of Edward Hopper, Balthus, Vilhelm Hammershoi and Gregg Toland, specifically his cinematography for Orson Welles in Citizen Kane. Alfred Hitchcock, Stanley Kubrick and Jean Renoir are with Welles at the top of the list of film-makers whose work resonates for years, constantly there, whether I’m conscious of it or not. As for writers, at the top of the list of influential and inspirational books is Joyce’s 'Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man'. James Agee and Alan Sillitoe join Joyce as inspirations, with Dickens for his capacity to conjure such vivid imagery and tell a story so well.

© Bill O’Donnell, Hot Plate

BO (continued): My very first experience of an artist’s immersion in the particular/personal with the improbable result being an observation on the shared ‘Human Condition’ was thanks to late Beatles songs by John Lennon. It was a lesson I’ve never forgotten: however alien we all might seem to be from each other, it’s also possible to tap into the totally opposite truth of our shared experience. Years later, I found quotes from both Anais Nin and Lisette Model echoing this notion that, the deeper one immerses oneself in the particular, the more one is likely gaining and sharing insight into the general.

JL: Currently on my studio desk are books by Paul Graham, Vija Celmin, Jem Southam, Robert Adams, and Roni Horn, along with “Ecology without Nature”, “Vibrant Matters”, and a collection of zen poems. My early photographic influences were works by Eugene Atget, Walker Evans, the Bechers, and Lee Friedlander, and although my photographs are not strictly documentary, I strive to make precise and descriptive photographs from direct observation with simple directness that could lead to a sense of discovery; they are records of my environments as well as my encounter with those sites. The influences of music and writers are more subtle and quirky. While I was editing a series of meditative and identically composed lake water pictures, I was listening to a lot of dance music in my studio. I think I needed the energetic beat of the songs to help me get through the arduous task of looking through stacks and stacks of photographs.

© Jin Lee, Great Water 17

I continue to maintain that geography plays one of the most important roles in the development of an artist’s work over the long term. Whether one is firmly rooted or more transitionally located in the world has its own impact. Related to this, I know that both of you have spent time commuting from Chicago to Bloomington/Normal over the years. Do these notions of geography play into your work?

BO: I grew up on Narragansett Bay, so my family would regularly drive to southern Rhode Island for beach fun and food. Inevitably, at some point during a day’s visit, my Dad would pull the car into a parking lot with an unobstructed view of the Ocean. The magic of seeing so great an expanse, seeing so great a distance, never left me. When I moved to Seattle and first visited a mountain top (I could walk over to a guard rail and look down onto the tops of clouds!), I felt that same god-like capacity to readily scan miles with a slight turn of my head. When I moved to Chicago, I knew I was on some damned flat terrain, but I was generally boxed in by buildings unless I was visiting the ocean-like Lake Michigan. When I first drove down I-55 from Chicago to Normal for the ISU job interview, I experienced a very odd, third manifestation of those first two examples of unobstructed view equaling an odd sort of understanding. At the ocean, lake or mountaintop, there’s an undeniable sense of the sublime, the alien, raw power of nature. The corn and soy fields of central Illinois can’t quite measure up, but there’s something wonderfully, perversely similar at work here; when the panorama before you consists of a uniformly grey expanse of sky, an equally uniform expanse of dark earth and a razor thin horizon line dividing the two, and that’s it, that’s all you can see. Well that’s pretty exotic stuff for a New Englander. I had just started my B&W ‘Home’ series at that point and this alien landscape strongly influenced the development of that work. I should add that, as far as I can tell, neither the hilly terrain of Providence nor the mountainous landscape of Seattle overtly influenced my work. It felt, in retrospect, like a culmination of this sort of rumination on the power of the distant view that I should perversely glory in the flatness, the relative nothingness of the industrialized prairie.

© Bill O’Donnell, Prairie

JL: My weekly two-hour drive on the flat Illinois land through changing seasons and weather has given me much to see as well as time to think. The ideas of a place and how its particularities shape one’s sense of self and the world have played a central role in my work. My family emigrated from Korea to the States when I was young; I grew up in California and went to school in Massachusetts before I settled in the middle of the country. I’ve come to understand that my landscape work of last ten year in part comes out of a desire to know and to love a place, and therefore to feel that I belong to that place. By paying attention to and photographing particular things over and over again, my goal has been to develop a sustained relationship and a connection to the place I live. The earlier projects focused more on the natural landscapes of the Midwest, including the prairie, but lately I’ve become fascinated by the scenes of human residues and weeds growing on the west side of Chicago. They feel as wild and mysterious as any natural sites, and just as beautiful.

© Jin Lee, Weed 3

You both began seriously working before social media and blogging became prominent. Is it useful or relevant to compare and contrast how photographs were encountered and discussed in a pre-web/blog era, and/or would you care to discuss your own experience interacting with photography in an on-line arena versus on the printed page or museum wall?

BO: I’m so tentatively participating in the new iteration of photography via blogging and social media that it’s pretty much confined to this: I daily receive a Lenscratch e-mail missive and I am at least 50% of the time, absolutely astonished by the quality of work that Aline Smithson is finding. With no disrespect intended to her, I have to conclude that there’s a whole new world of exciting photography happening out there and I’m resigned to the notion that I cannot keep up. But, at the very least, I’m curious about what the effect of the overwhelming volumes of imagery now being produced and posted on-line is and will be on the world of “fine arts photography”.

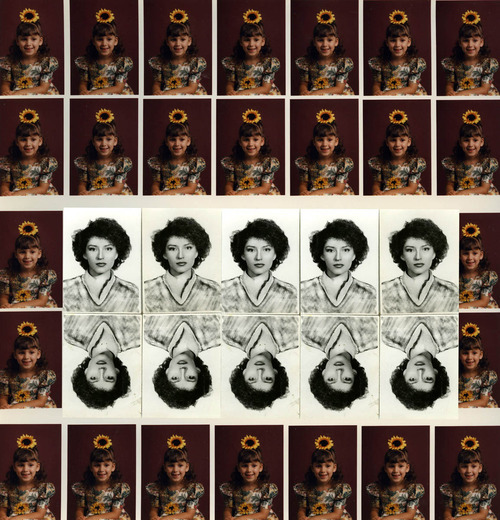

© Alex Hogan (student work)

JL: Access to online resources (blogs, archives, magazines, artist websites) has been incredibly helpful for my students and myself, especially because the University is located a couple of hours outside of a major city. We do, however, spend a lot of time looking at printed books (students have to go to the library and check out photography books to share with the class), and in addition to the excellent exhibitions at the ISU University Galleries, we make trips to museums and galleries in Chicago or St. Louis to look at artworks in person.

© Alex Hogan (student work)

JL (continued): There is a critical difference between looking images on screen and encountering photographic objects. I spend enormous amounts of time in my studio thinking about the physical presence of my photographs (size, surface, framing, space between pictures and their arrangements) and recently my students learned to make hand-bound artist books. In the time of easy and quick access to online images, a slower and more focused direct engagement with well-crafted objects seems necessary and important.

© Michelle Wallace (student work)

Building on the last question, have you noticed any changes in student work and/or how students work now that digital media is (generally) more prevalent than analog or alternative processes?

JL: Our photo curriculum starts with analog; Photo 1 class is entirely film camera and B/W darkroom, which the students love. I think it has to do with slowness and the physicality of exposing film and printing in the darkroom that lead them to a new understanding of how photographs are made and critical analysis of what they can mean. In the advanced classes, many students end up working digitally, but they are reminded to engage in the more conscious and heightened awareness that they practiced working with the analog process.

BO: When thinking about the differences between students’ working with analog vs. digital photography, I’m pleased that their first year in our program is all analog. The invaluable experience of making their way through a contact sheet, witnessing their own thought process in moving from frame to frame (with me looking over their shoulder, expressing preferences and questioning choices of exposures deemed worthy of enlargement) would be lost to them if they had the instant-access of an ‘erase’ button’. I think/hope that, by the time they’ve moved on to advanced level classes, this process of carefully charting their progress through to the solutions to expressive, esthetic problems has been nicely engrained by that earlier contact sheet experience.

Although I’ve yet to try it, I’ve thought that it might even prove useful to insist that advanced level students, working digitally for the first time, should be asked to avoid the erase button altogether (perhaps a piece of tape would be applied to the button as a reminder), so that we could then work our way together, through the progression of exposures, mimicking the contact sheet experience.

© Grant Walsh (student work)

Studying in the MFA program at ISU was influential to my development as a working artist due to its interdisciplinary nature. What are some of the differences between pursuing a BFA/MFA in an interdisciplinary college art program as opposed to a program solely devoted to photography?

BO: The accepted view is that the benefit of studying the fine arts in a University setting is that the student has so many more, so much richer an array of resources on which to draw than if enrolled in a program at an independent art school. In past years, I’ve been somewhat skeptical of this theory, convinced that the average student was so ‘burdened’ by the required class load of their particular curricular sequence that they barely even saw the interiors of any campus buildings other than the art building. However, I’ve gradually come around to the accepted wisdom…enough students do, in fact, find the range of possibilities offered by the University to be a rich set of resources that would otherwise not be available. If there’s no handy school in which a painter or photographer can study botany because it pertains to a body of work they’re pursuing, they take no botany class.

© Grant Walsh (student work)

In closing, can each of you describe or list one thing you’ve learned from each other by working together as friends and colleagues over the years?

JL: Gratitude for having such great colleagues - I really feel very fortunate to work with two photographers that I so deeply admire and have great affection for.

BO: I’ll absolutely echo Jin’s sentiment here. Before coming to work with Jin and Rhondal, I had no idea that faculty in a discipline area could possibly complement each other so well in so many aspects of their artwork, their approach to teaching and the countless ways in which that diversity of approaches contributes to the maturation of students/artists. We’re also fantastically collegial in conducting the business of running our area. Who knew friends could happen to have the same employer?

© Bill O’Donnell, Fireplace Slots

More about the MFA in Photography at Illinois State University. As a part of a multi-disciplinary graduate program within a large university setting, the MFA in Studio Art at Illinois State University is a three-year program that provides students with the necessary time and a supportive atmosphere to develop a mature body of work by exploring the relationship between active studio practice and rigorous intellectual inquiry. Every student accepted into the program is provided with a full tuition waiver and an assistantship for each of the three years. Located in Normal, Illinois, just two hours south of Chicago, the program also offers easy access to the vibrant museum and gallery environment of the city. In addition to an excellent faculty and extensive facilities, the School of Art offers students individual graduate studio spaces, visiting artist residencies and lectures, and University Galleries’ active exhibition schedule that provides a critical survey of contemporary art. The MFA in photography also offers an optional emphasis on documentary practice and theory, and students with a background in social science investigation are especially encouraged to apply.

---

LINKS

Jin Lee

Bill O’Donnell

United States

share this page