© Federico Clavarino from the series 'Italia o Italia'

Tell us about your approach to photography. How did it all start? What are your memories of your first shots?

Federico Clavarino (FC): My father has always been very much into photography (he published his first photobook last year, 'Magari'), so he gave me and my brother point-and-shoot cameras when we were still very young (I was 13 years old or so) to have some fun with. I found some of the pictures in a box some time ago, some of them are actually rather good. I quickly lost interest in taking photographs, I was a lot more into literature and music, and didn't take up a camera until I left Italy for Spain when I was 22. Mobiles could not take pictures then, so it was normal not to have a camera with you all the time, anyway I hated the idea of taking photographs of my own life, of my friends and special occasions. I thought, and still think, that photographs have a very special relation with memory: they change it, shape it, distort it, make us less capable of remembrance. In our mind the past keeps alive in a different way.

What got me into photography when I got to Spain was, at first, the need to communicate with friends and family, and mainly to illustrate writing. I enjoyed it so much I got into a course at BlankPaper Escuela (where I currently teach) because I felt I needed to learn how to get more out of my camera. That's when things made a sharp turn towards obsession. At the time I was working nights at a bar and teaching English lessons in companies during the day. I would spend long hours in the tube going from one lesson to the next, from one end of Madrid to the other, and often have a lot of time on my hands between lessons. I would find myself in some random part of town, and I would wander around with my camera taking pictures of things and people. It was a way of giving some kind of meaning to my time, a form to what I thought, and also a way of getting out of myself, projecting my gaze into things. I learnt how photography, far from being a mere reflection of reality, could be used to transform it, or at least to change the perception we have of it. John Szarkowski called it “a concrete kind of fiction”. I also started to be really interested in painting and sculpture, and particularly in the work of 20th century artists like Paul Klee, Mark Rothko, Kazimir Malevitch, Wassily Kandinsky, Laszlo Moholy-Nagy, I would read a lot of their writings, while also cultivating my interest in poetry, fiction and philosophy. Photography was just another tool for thinking, thinking through images, so I started discovering a mix of formal attributes of photographs I could play with, along with a series of ways I could start to use them in sequences. I have always read lots of comics, and that helped too, when it came to working with groups of images. That was also a time in which the constant feedback of my teacher, Fosi Vegue, and of my fellow students (Michele Tagliaferri, Victor Garrido, Alejandro Marote, Alberto Lizaralde, Arturo Rodriguez...they are all still active photographers and artists), played a fundamental role in shaping the way I started getting into photography.

The first little work I put together was called 'La Vertigine', published as a zine in 2010 by Fiesta Ediciones, and it was a short exercise in sequencing, based on a rather abstract idea (vertigo as a problematic relation with space and with reality), and that brought together a series of photographs woven together by mysterious connections. Something that could remind the way authors like Ralph Gibson, David Jimenez or Rinko Kawauchi, all of which were great influences for me, work with images.

© Federico Clavarino from the series 'La Vertigine'

How did your research evolve with respect to those early days?

FC: The following work, 'Ukraina Passport', was a lot more documentary and travel-based. I made a series of trips to Ukraine between 2009 and 2011, with the idea of making a work that would mix elements of history, politics and my personal experience of the place as an outsider, a bit like what Robert Frank did in 'The Americans'. What I found out was that I was incapable of getting as deep into the place as I meant to. I didn't speak Russian nor Ukrainian, and although I had studied the history of the place and delved into all the literature I could, there was a barrier I could not cross. My interest for the place had been something very spontaneous, I just happened to be in Odessa after failing to make a short documentary in the Danube Delta, and fell in love with the place. There was something I felt there that I just had to make into images. Then there came along all the thinking about Ukraine's Soviet past and consumerist present, and all the tension between Russia and the EU, all the politics and the history that came oozing out of things and people (at least those I could talk to). The photography, I felt, was constantly falling short of my intentions. I wanted one thing and another came out. The work ended up looking more and more like something private, discreet, some kind of “carnet de voyage”, and less and less like this documentary fresco I wanted to paint of the place. I guess in this I ended up being more faithful to the initial feeling that had given impulse to the work.

© Federico Clavarino from the series 'Ukraina Passport'

Compared to 'La Vertigine', 'Ukraina Passport' is a lot more down-to-earth, it is colour photography (the other is BW), formally less consistent, but in my opinion more alive, more loving. There is something very spontaneous there I do miss a little bit nowadays.

'Italia o Italia', the following body of work, was born out of the need to work in a more familiar territory and also to reconcile myself with the culture I was born and raised into, and with the place I had left a few years before. I dare say I consider that as my first mature work. The formal research that had started while I was studying found its completion there: the simplicity of form, the balance, the colour palette, the opaqueness of the pictorial surface. On another level, the work was strongly symbolic, it managed to evoke more than what it stated, and at the same time to bring together a series of cultural references without (in my opinion) being too obvious. Structurally, 'Italia o Italia' is very strictly organised and sequenced around an archetypal model, the labyrinth. Maybe too structured, now that I can look back to it from a distance of two years, which means that now I am trying to work with looser structures, although it is difficult to find the right balance: you go one way and it becomes ambiguous, you go the other and you squeeze the life out of it.

© Federico Clavarino from the series 'Italia o Italia'

I must say I am very happy with my last book, 'The Castle', that only just came out. I feel it flows very well, and that a right balance is achieved between form and function, depth and clarity. But time will tell, as it always does. I feel the work is the end of a first exploration in photography, it shares many things with all of the previous works, but puts them together more effectively in my opinion. So now I am trying to somehow change direction, and for the last two years I have been working on something a lot more narrative, called 'Hereafter', with a different, slower, camera, and integrating more text into the work (apart from a little bit of text at the end of 'The Castle', all the other works are literally textless). I feel I want to speak a more human language now, there is a lot of loneliness in the last two works, maybe a certain coldness, although I do think they are lucid works, especially 'The Castle'. So in 'Hereafter' I am working with a family thing, which could be a nice start towards a new direction. At least I hope so.

You have studied creative writing and narrative techniques before moving to Madrid and taking up photography. However, there is almost no text in any of your finished projects. I can imagine writing has been an essential tool throughout the process but that it becomes obsolete when you reach the final stages of a project. Can you tell us a bit more about your relation to these two languages of expression?

FC: In my first two books I tried to avoid the use of text as much as I could. In 'Ukraina Passport' I even tried to avoid using a title, the name of the book is just what is inscribed in the object that contains the work (a passport). In 'Italia o Italia' the title is meant to work a bit like an image, especially on the spine; it is a key to what is inside, to the structure of the book. The rest of the text is what the law required me to include in the book: the copyright, my name, and the year it was published. I did so because I believe that, although one could say that an image is text and that text is always an image, culturally they have different uses and roles, and nowadays text still prevails over images. A title is enough to impose a reading over a series of images, text in general limits the way we access images, it provides a context for them. Photographs in particular are very enigmatic objects, extremely open to interpretation and manipulation. This been said, writing has always been a fundamental tool for me throughout the process (I take many notes), as is reading all kinds of written material (literature, philosophy, poetry, art theory...).

Book 'Ukraina Passport' published by Dalpine, 2011

© Federico Clavarino from the series 'Ukraina Passport'

In 'The Castle' text is more present than in other works, each chapter has a title and is opened by a proverb. The proverbs here work a bit like the photographs: they are banal fragments of everyday reality, words that have lost their meaning by being repeated too much, exactly as the things you stop looking at when you see them every day. My intention, as with the images, is to displace them and insert them within another context capable of revealing their problematic aspects. It is when the everyday is made strange that you start thinking. 'The Castle' also includes notes at the end for each chapter. Each of them work differently, depending on the chapter, and they are meant to broaden the scope of the work, sometimes to allow for a deeper reading, and in other cases to take the reader to other books. A book is always an opening. The idea here is that the images walk you through the book, and the texts at the end take you back to the images, thus allowing for a different reading. In the project I am working on right now, 'Hereafter', text will be very present, and it will constantly work with the images, not as much to explain their content as to generate little explosions of meaning.

© Federico Clavarino from the series 'Hereafter'

Although you’re not afraid to get up & close with (and under the skin of) your subjects in order to photograph them, a sense of distance or alienation is always very present in your images. There is a lack of interaction between yourself and the subject which makes you as a photographer invisible in the photographs. You start from keen observation in order to recognize situations that evoke or represent the theme you had in mind. Do you feel slowing down the process when working on your current project ‘hereafter’, both by searching for a different photographic technique as by writing, is necessary to approach this more familiar and intimate theme?

FC: Yes, I do. Up to now, I have always had a flanêur's approach to the act of taking photographs. I walked around with a 35mm camera and after a while I always entered a special zone in which things became incredibly distant and very near at the same time. I felt I could walk up to someone and start taking close shots of their faces and that would be normal, though no human contact was really established. People became part of what I was seeing, I would become the spectator of my own experience. The alienation this caused would also fuel the conceptual base of the work, as well as the feeling of loneliness and distance evoked by the images. In Hereafter this could not be the case. It is both a very personal work and a very tricky one because of the sensitive political nerves it touches. I needed to slow down the process and work with a view camera to be forced to confront people, to generate a different kind of fiction, one in which there is a dialogue. I am not only talking about portraits, also when looking at something for a long time through the ground glass there is something that comes back the other way. You look and something looks back at you. It might sound absurd but it is something I feel.

How was it like in the beginning to become a teacher yourself after only two years of having finished your master course in photography at the same school? Did it change the way you worked? Would you encourage other photographers to go through the experience of teaching?

FC: What I feel is that when you teach something you are made to confront the subject more deeply and above all to know it more clearly. In the first place, this meant that I had to start studying again. There is a constant flow of ideas between what I research, what I teach and what I do. It keeps it all very alive. I change the syllabus every year by introducing things I have learnt both by studying and by making work as a photographer. At the same time, what happens in class with my students obliges me to face aspects of photography I don't usually work with. I learn things from the students, a lot of them can do things I cannot do, which often motivates me to try to integrate something new in my own practice. I don't know if I would encourage other photographers to take up teaching, though. It is something you need to love, and it can also be very frustrating. You need to know how to listen to other people's needs and intentions and try not to impose your view of it, when it comes to their work. On the other hand, you have to avoid being paternalistic. Many great photographers I know wouldn't necessarily be good teachers.

In an interview with Fotografia Magazine you mention that seeing your mentors go through their creative process made you realise that the only way to get results was to work hard. You are now a teacher yourself. Do you share your own creative process with your students?

FC: I do, but I try to avoid doing it very often. I feel they need to discover their own creative process they are comfortable with. This is why it is good for them to see the works of different photographers and artists, so they can pick here and there and come up with something they feel their own. Still, I do believe hard work is always necessary, and there are too many books nowadays that would have been a lot more interesting if the author had put another year or two's work in them. It is very easy to publish and exhibit nowadays, there are hundreds of festivals, institutions, small publishers, awards, portfolio reviews and so on, which is a very good thing, but combined to the use of social networks this also creates a very narcissistic community, fuelled by a constant flow of often mediocre work.

Both 'Ukraina Pasport' and 'The Castle' find their origins in the attempt but failure of working on something else. In case of 'The Castle' even an entire part, which consists of double exposed negatives, has been fruit of a happy coincidence. It’s sometimes good to be reminded that everything will eventually lead somewhere or at least that it’s necessary to find a balance between failure and success in order to move forward. What, in your experience, are the good and hard parts of being a photographer?

FC: Photography often forces you to confront reality, and reality is unpredictable. There is only so much you can control, and often the most interesting qualities of a photograph are the ones that exceed the photographer's intentions. Something similar happens with entire projects. You set out with a bunch of ideas and start working, but experience always challenges those ideas, and this usually ends up showing you how it all is a lot more complex than you thought it was. Then there are accidents, like what happened with the double exposed negative in chapter one of 'The Castle'. I must confess that when I realized the roll had been exposed twice I was mad at myself. It was just a mistake, nothing more. But for some reason I made a contact sheet of it and kept it. It was four or five years later I stumbled upon it and used it to give a structure to the chapter. I guess part of the artist's job has to do with knowing how to recognize potentialities in what to others may just look like mistakes, or insignificant events. That is the good part. The hard part is that this also means the work never really matches your expectations, it is always beyond your control. More often that not, it just feels it's not right, it's not as good as you wanted it to be. What you had imagined was a lot deeper and complex than what came out. Beckett famously wrote “try again, fail again, fail better”. That is what it feels like, every work is just another failed attempt. The next one, hopefully, will be better.

© Federico Clavarino from the series 'The Castle'

So far, every project you completed resulted in a book. Have you always envisioned it like this? Is a book the ideal space for presenting a photographic work? What do you take in consideration when working on a book?

I discovered books when studying at BlankPaper. Fosi Vegue would show us books and we would analyse them together in class and I remember it opened up a world to me. I had never imagined you could work with sequences that complex. Before that I had seen exhibitions, and catalogues, maybe a few proper books, but as many others I would focus on single images or short series. To discover works like Frank's 'The Americans', or Koudelka's 'Exiles', the classics of documentary photography, was a profound experience, and to learn how to read them was a point of no return: I saw endless possibilities within the book, as many others did and still do. The book is a way of providing a context and an order to objects that are otherwise extremely open, for example photographs. A book has pages, and because of that, it has a rhythm of its own. A book has a beginning and an end. It has a cover, and a spine. All of that matters, all of that limits and contains the work, and at the same time it can be used to make it more powerful, to endow it with meaningful space. There is space and there is time within a book. You turn its pages and look, then turn again. You can go back, when something reminds you of something you have already seen. It gives the reader freedom to leaf through it many times, back and forth. I don't know if it is the ideal space for presenting photographic work, but it is the one I enjoy the most right now. There are works which I feel are best at home in a book, others on a wall, or in other contexts. I find it also very interesting to adapt the same body of work to different spaces in very different ways. An exhibition seldom works if it is the translation of a book on the wall, exactly as a book seldom works when it's a catalogue for an exhibition.

Book 'The Castle' published by Dalpine, 2016

© Federico Clavarino from the series 'The Castle'

I have tried to do something similar with 'The Castle', recently, at Madrid's Círculo de Bellas Artes, within PhotoEspaña photography festival. I had a room at my disposal, so I decided to keep the chapters but play them out very differently on the walls. I also decided to integrate a sound installation a friend, Julián Mayorga, designed for the exhibit. Interestingly, the part that a few people found less powerful was the one that resembled the book the most. The same body of work was brought to other spaces, Temple in Paris and Viasaterna in Milan. At Temple it was a solo exhibition in a very small space, which called for a very immersive experience, while at Viasaterna the work had to be displayed within a collective exhibit and dialogue with the work of others. The curators also played a fundamental role in making decisions for the layout, that ended up being very different. Exhibits are usually ephemeral, which mean you can try different things in different spaces, which is liberating when compared to something more fixed like the book form.

Three books (photobooks, art books, literature) that you recommend?

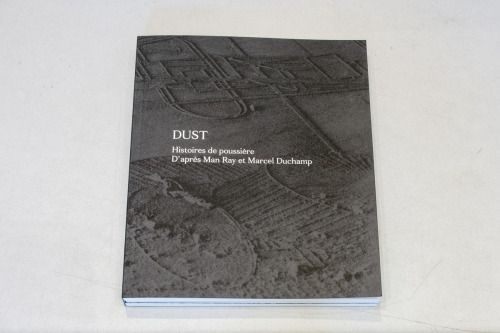

FC: As for photobooks, it is rather difficult, as many of the books I love are now very hard to find. It is a shame that classics of the genre are made inaccessible to its public by the characteristics of the market: it is very expensive to print and distribute a photobook, plus the market is very small, so the print runs are short, which means retail prices are high and the ones that are successful quickly disappear and end up prey to speculation. I would never recommend to anyone to buy a book for more than 100 euros, so I will recommend one I love and that can easily be bought: 'A Handful of Dust' by David Campany. It is an exciting adventure into photography, art history and wonderful writing. It is also a very special object, combining a sequence of images with text very successfully. You can read the images, then the text, bounce back to the images, it's brilliant.

© Book view ‘A handful of Dust’ by David Campany, published by MACK books 2015

© Élevage de poussière, Man Ray et Marcel Duchamp, 1920, Courtesy Galerie Françoise Paviot

As for literature, there are so many books I would recommend that I'll go for one of the last ones that have really blown my mind, W.G. Sebald's 'The Rings of Saturn', in my opinion his finest. It is a very special book, combining different times and places, a true hybrid of a book, one capable of mixing true facts and fiction, biography and myth, photographs and text.

The third book I would like to recommend is a graphic novel, I have always loved comics and I believe there are people out there doing incredible work nowadays, and it is a shame that, as it is even more the case with photobooks, they do not reach the audience cinema or traditional novels do. I also believe this is changing for the best. The book I want to recommend is not exactly a book, it is a box, it is called 'Building Stories' and its author is Chris Ware. He is an incredible storyteller, and because of the peculiar form the work comes in (a series of narrative objects you find in the box), he manages to propose a new way of relating to the space and time of a story: you are responsible for the flashbacks and ellipses, depending on which object you pick up. It is you, as a reader, who builds the story you find in the box.

Is there any show you’ve seen recently that you find inspiring?

FC: I will mention two. One of them is a retrospective of the work of Ulises Carrión, a Mexican conceptual artist that lived and worked in Amsterdam for most of his life. Although often I found the work a bit shallow, the exhibition was really inspiring. Carrión was an incredibly productive artist, and he covered all of the creative process: from conceptualization, to production and distribution. He would work with performance, with text, with text as an image, with books as objects, with video art, but then he also had this bookshop called “Other Books and So”, that he would use as a base for all of his operations, and to sell books from other authors. He was creating a context from scratch, and I find that extremely liberating. Artists often work within established spaces: galleries, museums and the like, publishers. It is a huge limitation and something that must be challenged. Another thing I loved in the show was his research about gossip and rumors. It is wonderfully fun, and also very intelligent.

© Goshka Macuga, To the Son of Man Who Ate the Scroll, 2016. Photo: Delfino Sisto Legnani Studio

The other show, which I saw at Fondazione Prada in Milan, is called 'To the Son of Man Who Ate the Scroll', by Polish artist Goshka Macuga, who takes on the roles of artist, curator, researcher and exhibition designer to work with different media, objects created by other artists and things of her own making to address themes so big as time, history, and the end of mankind. In one part of the exhibition she uses works by sculptors like Fontana, Giacometti or James Lee Bryars, as a setting for an android that claims to be “a repository of human speech”, and that seems to talk to you with an earnest expression about deep philosophical issues and contemporary problems. The chilling thing is that its monologue is made up of a series of recordings, and the robot could continue talking for ages to an extinct mankind. I found that extremely powerful.

LINKS

Federico Clavarino

Italy

share this page