© Edoardo Hahn, Milano, Italy, 2016

Talk to us about how you started photography. What do you remember about your first photographs?

Edoardo Hahn (EH): It seems like I have been doing photography for as long as I can remember. I have always considered it the best way to be confronted with the reality surrounding me. Images force you to see the world in a different way. They force you to reflect upon the appearance of an object, a landscape or a person you are looking at.

More so than my first photographs, which I don’t have clear memories of, I remember my first project for school. I was 12 years old at the time. It was given to us by our teacher as a summer assignment. We had to tell a story with words and images about the place where we spent our holidays.

How has your approach to photography evolved throughout time?

EH: Well, a lot of things have changed. I studied photography, evidently not only from a technical point of view, but mainly its ability to communicate. It has always been a slow unpredictable progress, marked by episodes of moving forward and sometimes taking a step backwards. I am self-taught, which means that I myself have worked on my background piece by piece. Seeing that I haven’t had a specific cultural influence to fall back on I don’t have precise rules to follow. I have been practicing photography for at least 40 years and I am progressively more interested in elusive and ambiguous subject matters.

© Edoardo Hahn, Sacramento, USA, 2013

Which authors, not exclusively in the field of photography, have influenced and accompanied you throughout your personal experience in the past and now?

EH: Every photographer has a continuous flow of images in his mind. Besides his own, also those shot by others, from which he repeatedly draws inspiration to create his own photographs, making new associations and rearranging them continuously. My own flow consists of images from the great classics of American color photography from the ‘70s: Stephen Shore, William Eggleston, Lee Friedlander, Fred Herzong. However, others have had an influence too, ranging from Daido Moriyama to Geert Goiris. I have always been very eclectic and have drawn inspiration from contradicting sources.

© Edoardo Hahn, Brest, France, 2007

Let’s talk about your present research in photography. How would you define it? What are your interests? How do your projects develop?

EH: My research is situated in the field of landscape photography, in search of giving meaning to reality around us and the progressive impossibility of that rationalization. I would define photography as a physical and metaphorical journey undertaken by the photographer, who seeks to investigate the singularity and the enigma of that which he observes in front of him, however mundane it might seem. By means of a sort of optical migration following his own gaze the photographer chooses the person, the tree, the stone or the building or whatever he decides to capture. My projects emerge from the collision between that piece of the world that I’ve chosen to photograph and my inner world.

The debate between analog and digital still produces lively contradictory opinions. What is yours? Which method of photography do you prefer?

EH: It depends on the project. Seeing that I use digital as well as analog and change from one to the other effortlessly I don’t have a method that I prefer. It’s a debate that doesn’t stir a passion in me and that I consider to be a little phony. When I have a potentially interesting idea I pursue it with the means that I believe offer the most opportunities and those depend on the type of project, not on a decision a priori regarding technique.

In 2013 I had the pleasure of meeting you and to curate an exhibition on your work ‘Forest’. At the time I described your photos as “thinking machines”. Could you talk to us about that project.

EH: It concerns a project that stayed with me for many years. The topic was forests, more precisely the way in which they appear to us and how we imagine them (the fantasies that we project on them). Those pictures don’t focus on one specific location or forest, nor are they a representation of nature. They regard a concept of loss of focus and significance. They are like screens or invisible images; there isn’t a means of escape, which allows us to see the image in perspective. There isn’t a before and after, nor a story to tell. It’s a process of immersion. When confronted with a photo of undifferentiated vegetation the onlooker’s mind does not have one spot to fixate on therefore he aims his focus towards himself.

© Edoardo Hahn, Celle Ligure, Italia, 2014 from the series 'Forest', 2009 - 2014

© Edoardo Hahn, Celle Ligure, Italia, 2013 from the series 'Forest', 2009 - 2014

Recently you have renovated your website. Differing from what we are used to seeing, it allows a slow immersion to which one can surrender without being swallowed, omitting an index and key words, commissioned and personal work are intertwined giving life to your own poetics. Could you talk to us about that choice?

EH: I had a website with a standard layout in which every project was clearly indicated, enclosed in their pretty box, properly wrapped with an unequivocal clear-cut meaning. In my head, however, this didn’t stroke with reality. Images of a project end up in another, which in its turn continues into a third one and so forth. The associations between the images change with time and develop different interpretations. The web is the birthplace of this kind of thinking. During the last years of the '90s I had created a hypertext with quotes, which I had gathered in a database connecting them with expressions from different authors only by means of the logic of the hyperlink. So for me, how we observe the website now is the continuation of this study and this way of thinking.

© Edoardo Hahn, Belo Horizonte - Salvador de Bahia, Brasil, 2015

© Edoardo Hahn Salvador de Bahia, Brasil, 2015 - Tokyo, Japan, 2010

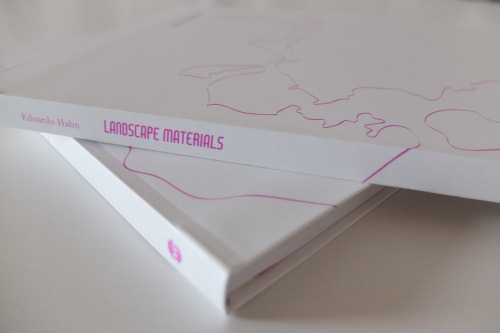

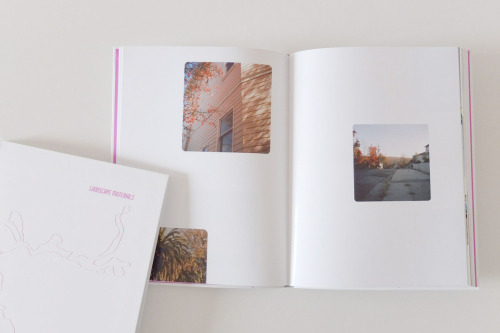

Recently you have published your first monograph 'Landscape Materials’ in the new book series 'Urbanautica Collections’ edited by L'Artiere. We have worked almost 2 years on its creation. You know very well that I’m convinced that this is a matter of a courageous operation that will leave an unequivocal mark on the field of editorial production of landscape photography. Could you talk to us about this experience?

EH: It was without a doubt intense. I have had the opportunity to challenge myself as a producer of images. Everything started with a series of pictures randomly taken in the northern zone of Bay Area in California. This also reflects the process of the project; a drift in a landscape that I didn’t personally know, only through cross references that could come to mind (from books, movies, music, series etc.). Once I returned and took on the responsibility of the project again, I firstly tried to go about it the traditional way, that is one picture after the other in the same dimensions. This, however, didn’t do much for me. At that point you came into play and we started to confront each other while listening to the same music I was listening to during my personal drift in the area. The music has been very important in the construction of the layout, allowing to put a rhythm in the seemingly casual flow. From this sprung a book that implodes and does everything except tell a story. A collection of sketches isolated and juxtaposed events that achieve nothing, pieces that don’t meet and happenings without reason or conclusion. In this sense the author ends up disappearing into the scenery accepting the natural complicatedness and sheer chance of things.

© Book ‘Landscape Materials’, Urbanautica Collections, published by L’Artiere

Just like Nicola Braghieri explains very well in one of the two texts accompanying the volume; the term landscape was originally meant to indicate its representation on canvas not the actual landscape. In other words the concept of representation, of appropriation of a form by the painter or the photographer manifests itself in the semantic nature of the term. In this respect the separate photos lose their value as a testimony of a specific geographic location. Fluctuating in accordance to the mood of the observer they are images reflecting ambiguous coordinates. It’s out of this that the volume’s specific layout is born as a sort of visual trip underlining the difficulty that we today have rationalizing a by now fractal landscape with an indefinite meaning.

© Book ‘Landscape Materials’, Urbanautica Collections, published by L’Artiere

Over the past few months we have reflected on the expositive modality of this project. What are your impressions?

EH: I think that it’s a requirement to follow the laid out path starting with the creation of the website and consequently moving on to the production of the book. The idea that we are working on is that, just like in the book, the images break free from the pages and probably also from our own comprehension. In the expositive modality something similar should happen with the images that break free from the space of the frame and occupy the entire illustrating space. How to make all of that happen will be our next challenge.

© Book ‘Landscape Materials’, Urbanautica Collections, published by L’Artiere

---

LINKS

Edoardo Hahn

Italy

share this page