Detroit is becoming a cultural symbol for the failed American Dream. In your series 'Detroit – Unbroken Down' you seem to be pointing to the small creative acts of individuals as an antidote to that notion.

Dave Jordano (DJ): It’s no secret that Detroit has suffered a slow, steadily progressive, economic implosion. Hundreds of articles, newscasts, webzines, blogs, and photographers have reported on the city and essentially focused on the blight and its decades long tumble into decline. Recent census figures report that Detroit’s population has now shrunk to 714,000, or roughly what it was 100 years ago. In the last decade alone its population has declined by more than 25%. In contrast, sixty years ago Detroit was the fourth largest city in the nation with a population of over two million inhabitants. What’s left today is a city stretching 140 square miles with enough empty space that you could fit all of Boston or San Francisco within its vacant lots.

That being said, this work is a reaction to all the negative press that I felt Detroit has endured over past few years. It became apparent to me that what others were overlooking was the human condition, the heart of what a city is all about, the people left to cope with the harsh realities of a postindustrial town that has fallen on the hardest of times. It’s the many small neighborhoods that make up a city, not the empty industrial plants and factories that corporations have abandoned and turned their backs on. Within these neighborhoods is a wonderful array of individuals and groups that make up the social, ethnic, and racial fabric of a city. As a photographer you might say that I’m interested in the cultural anthropology of what makes up the city.

© Dave Jordano from the series 'Detroit. Unbroken Down', Algernon with His Pet Dog Babe, Moran Streeet, Eastside, 2010

© Dave Jordano from the series 'Detroit. Unbroken Down', A Woman Sleeping in a Parking Lot near East Warren Avenue, 2010

© Dave Jordano from the series 'Detroit. Unbroken Down', Fourth of July, Belle Isle, 2010

What is your approach regarding choice of locales in Detroit?

DJ: There isn’t an area of the city that I feel doesn’t have potential for this project so I’m open minded as to where I find myself traveling. I do tend to be drawn to neighborhoods that are the most disadvantaged. These are the people who haven’t a choice as to whether or not they can leave the city. Their situation is compliant on their economic condition, which precludes them from doing so. This doesn’t necessarily create a negative, as it often forces creative solutions for those who live in these depressed areas, like planting community gardens, bartering for services, and setting up local help organizations, or just figuring out how to survive. These are the neighborhoods that intrigue me the most because they’re most likely the hardest ones to find something positive about. Since the housing market collapse in 2008, the onset of abandonment in even the most affluent neighborhoods of Detroit is becoming evident, so there really isn’t an area of the city that hasn’t been affected by the long or short-term economic decline.

© Dave Jordano from the series 'Detroit. Unbroken Down', Cricket Game, Eastside, 2010

© Dave Jordano from the series 'Detroit. Unbroken Down', Angela and Aya, Brother Nature Community Garden, North Corktown, 2010

Describe your process of reacquaintance with your former hometown through this project?

DJ: I first came back to Detroit last spring in 2010 after a three-decade absence. My early life revolved around Detroit. Many of my relatives were also still living in Detroit back in the 60’s and 70’s. My parents, my aunts and uncles, cousins, my brothers, friends, all of them were in some capacity working within the auto industry. If you didn’t, you were considered odd. The economic depth of GM, Ford, and Chrysler was so far reaching that practically everyone’s livelihood depended on the “Big Three.” It was a time of great economic prosperity for everyone. Not just for the white collar workers, but the blue collar trades people and the factory assembly line workers as well. We were all living the American Dream. This is how I remembered Detroit. It wasn’t until I started reading all the negative press about the city that I took an interest again. Initially I was drawn to the same things that other photographers were interested in; the abandoned buildings, the empty lots and burned out houses, and the massive empty commercial and city structures. It took me a week of shooting this kind of subject matter to make me realize that I was just beating a dead horse. I was contributing nothing to a subject that everyone already knew much about, especially for those who had been living there for years. I didn’t have a good feeling about this way of working as it felt as if I was, in a sense, betraying my hometown. To counter this, I started looking at all the various neighborhoods around the city and the people who still live in them. There was life here and movement, not just the death and decay that everyone was showing in the media. Perhaps there was also something of my earlier days here to rediscover, something in my collective memory that I could cling to. A fantasy thought for sure, but these early memories became the catalyst that got me thinking about this project and the direction it took. Of course Detroit has its problems and I don’t profess to see the city through rose-colored glasses, but without some kind of counter balance there will never be an opportunity to see another side of the story.

© Dave Jordano from the series 'Detroit. Unbroken Down', Glemie Playing the Blues, Westside 2011

We become connected to the sidewalks of these Detroit neighborhoods and see everyday life as acts of faith, and here I am also referring to your seriesArticles of Faith.

DJ: Yes, I think there is a direct correlation between these two bodies of work. The act, or feeling of faith can manifest itself in many forms, not just a religious one. Faith in ones own self can be as powerful as ones faith in God. What these works share in common is a sense of belonging brought together through common associations. They both are about people who come from similar socio, economic and urban backgrounds where life is hard and lived out day to day. The Chicago church project dealt with one specific form of how people practice their faith, while the Detroit work covers a broader range of experiences, but the underling message for both is one of hope and perseverance.

© Dave Jordano from the series 'Articles of Faith'

© Dave Jordano from the series 'Articles of Faith'

© Dave Jordano from the series 'Articles of Faith'

Do you think you will continue to expand this project into other facets of Motor City?

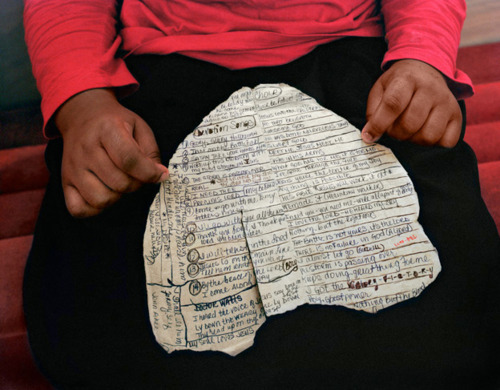

DJ: I have a few other ideas that could be linked together with this work, but what has caught my attention in the few trips I’ve made so far to Detroit is the unusually high number of white women on the streets engaged in prostitution. Their brazen attitude and overt behavior shows that they have little or no fear of the police. I’ve not seen this kind of behavior in other major cities, especially in broad daylight and on the level with which it occurs in Detroit. As it turns out they are all victims of substance abuse, almost all of them being heavily addicted to crack cocaine and heroin. The Detroit police force is severely short staffed and stretched to its limits. I believe they view prostitution as a low priority crime. As long as there isn’t violence committed against law-abiding citizens, they tend to ignore it. This creates a lucrative environment for crack houses and dope dens that perpetuate the existence of addiction and prostitution. A lot has been documented about this subject. It’s an age-old problem. My approach is to photograph these women in a way that your perception as to what and who they are is slightly thrown off. You’re not sure what the meaning of the photograph is. In this sense they could be considered just normal people, perhaps a friend or relative, someone close to you or a loved one, but in reality someone caught in a very bad situation. I want to show that these women are just like you and me. I hope this approach will make the viewer realize that these women are victims, not criminals, and will help remind us of the fragility of our own demise by bringing awareness to how easy it is to lose one’s self.

© Dave Jordano from the series 'Detroit. Unbroken Down', Lisa, 2010

In primarily what final form do you envision this project?

DJ: Good question, but first I have to complete the project, but in the end a book would be my first response, (don’t we all want books published of our work), and then some exhibition opportunities for sure. The Internet is one of the most powerful and easily accessible ways to get your work out to the viewing public, and this is my method at the moment. Even though I consider “Unbroken Down” a work in progress, the urgency and timing of getting out what I had already completed seemed the more appropriate thing to do, considering what most people thought of what Detroit represented.

---

LINKS

Dave Jordano

United States

share this page