Ann Shelton (MFA, The University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada) is recognized as one of New Zealand’s leading photographic artists and in 2010 was the overall winner of the CoCA Anthony Harper Contemporary Art Award. Shelton lectures in Fine Art and Photography at Massey University in Wellington and is currently Chairperson of Enjoy Public Art Gallery, Wellington’s artist-run space. She is represented by Starkwhite and Paul McNamara Gallery.

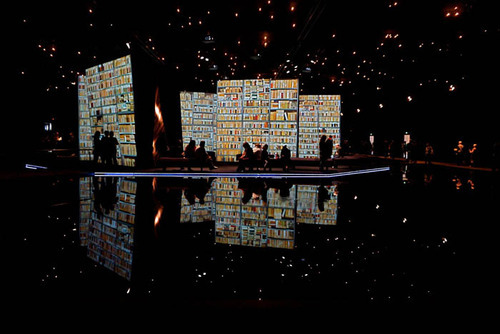

© Ann Shelton, In a Forest, Australian Center for Photography, Installation View, Sydney, Australia, 2012

We met at a conference titled Framing Time and Place: Repeats and Returns in Photography, in 2009. Can you briefly discuss the paper you read at that conference, and how its concerns play into the history of your practice as well as your current work?

Ann Shelton (AS): Photography is a medium of semblances, of multiplicity and fractured realities. InTechniques of the Observer Jonathan Crary suggests that doubled images echo the sense of reconciliation of the similar but not identical images seen by each eye. [1] Two or more images speak of serial reproduction, of repeats, of twinnings and of a particular experience which constitutes a slippage from monocular vision and foregrounds the role of the camera in the construction of fields of representation. A significant aspect of my artistic practice has been a concern with the development of a particular signification system, of an ocular language and a formal methodology outside of the normative singular presentation of photographic images. Specifically, at the time we met, I was interested in the use of doubling, pairing, coupling and inversion and in how these formal devices could be used to disrupt a particular dominant and singular visual system. I was interested in how this kind of visual stammering might change the cognition or reception of images conceptually and physically – suggesting an uncertainty, a violence or a kind of duplicity.

© Ann Shelton, Doublet, (After Heavenly Creatures) Parker/Hulme Crime Scene Port Hills, Christchurch, New Zealand, 2001 Diptych, C type prints, 720 x 900 and 1200 x 1500 mm each

So at the conference, rather than come at things from the perspective of the re-photographic movement, for example in the works of keynote Mark Klett, I came at it from the perspective of presenting and discussing the idea of the duplicated variant photograph: some kind of aberrant double. I used the work of Roni Horn, Felix Gonzales Torres and my own artwork to progress a discussion of this area. I was also interested in the reversed double and in its status as an impure or inverted copy and in how an artist might use the device of an inverted image to disrupt the intent, the authenticity, and the surety of a singular view.

Since the conference (2009), I have continued to use doubling as a device to confound viewership in some instances and as one device in amongst other visual methodologies. In my series Room Room, I used a visual reference to the Claude glass as a way to talk about vision and visual manipulation, making a series of images that referred to its often circular and distorted Tondo format. More recently I have become interested in single images again (although they are activated in some way), along with various applications of negative or inverted images. I am still very much concerned with the field of visuality and with producing images that make the formal aspects of photography, that we take for granted, more visible and present to a viewer. Some of my new work also seems to have taken a step further away from what could be perceived as a more “direct” relationship to documentary, abstracting out from traces or objects that have a more tenuous relationship to a “factual” narrative.

Left: © Ann Shelton, Heavy Metal, Platinum, recovered scrap metal from the remains of the decommissioned Wanganui Computer, 2013 (work in progress). Right: © Ann Shelton, Heavy Metal, Palladium, recovered scrap metal from the remains of the decommissioned Wanganui Computer, 2013 (work in progress)

Leading nicely into your next question, I have been interested in that juncture between fiction and reality, between tableau and slice of life, between journalism and art, for some time now – my work interrogates these complexities and investigates the grey areas between them. Currently I am experimenting with chopping up photos – not sure where that’s going – but formally intervening in the surface of the image is another opportunity to disrupt its finality. I like the idea of propositional photographs, what I have called elsewhere a kind of visual stammering. My use of pairs, copies and duplicates help solidify a sense of instability when one visually encounters one of my works.

I know that you have a background in photojournalism. Do you see that mode of working as being distinct from fine-art photography, or are there areas of overlap that you draw from in your current work?

AS: I am interested in both conceptual & documentary photographic modes of image making. The documentary impulse has been represented consistently in my practice to date, whether it’s via subject matter or formal intervention at the level of the surface of the work and/or in the process and methodology of its making - however removed. Being a press photographer and the ethical and political problems associated with that role were formative for me as a young artist. We can obsess about what is art and what is a document however these arguments are ultimately limiting. I can think of documents that are art and art that is a document. What is more interesting is getting past this and thinking about how artifice is manifest in journalism and how this blurring of boundaries is manifest in contemporary art. What might the potential of those more complex positions be and how might they have an agency? I’m thinking here about reenactment as a device in contemporary art works which engage documentary issues, such as Jeremy Deller’s Battle of Orgreave, or of the use of a narrative in Tacita Dean’s Teignmouth Electron, these works use historical narratives as jumping off points for the creation of an artwork. You could say they recognize any sense of ‘reality’ as lost, manipulated or transformed through the actions of history and memory, simultaneously they also recognize the power and significance of events. Geoffrey Batchen said recently in The Brooklyn Rail “Picture a history of photography freed from the tyranny of the photograph.” [2] For me Batchen is pointing out the potential of photography. What happens when it ceases to be clung to as a mimetic device? What does its history and potentiality look like then?

© Ann Shelton, a library to scale, New Zealand Pavilion, Frankfurt Book Fair, Germany 2012, Installation View (Photo credit: Lisa Gardiner)

From what I know of several of your projects, your photographs seem to be very much contingent upon the intensive research process that precipitates the work’s creation. Where did your interest in archival source materials stem from, and what role does this kind of research play in your process?

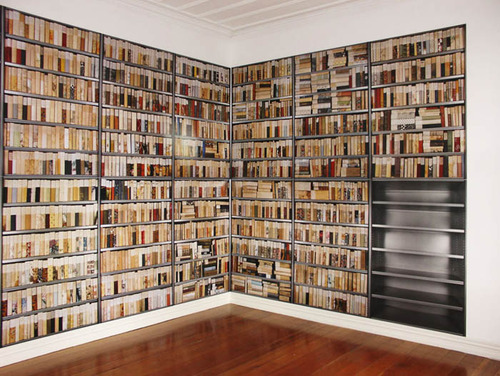

AS: It seems I like pieces of paper. I am going to answer this question initially with a quote from Jan Bryant who is discussing my project a library to scale (pictured above).

© Ann Shelton, a library to scale, Starkwhite Gallery, Installation View, Auckland, New Zealand, 2006

In terms of research, this is a significant area of focus for my practice. Photography is a surface medium, and in a sense, my assembling of research around a site or object is an attempt to thwart that lack of information that the photograph communicates, or to focus the type of information a photograph gives about a site or object in new ways. So over the last 10 to 12 years I have investigated the ways in which supplementary information can be introduced to a photograph. I’ve used super extended titles, publications such as newspapers that accompany a set of images and recently I have been experimenting with QR codes imbedded in images. Because my work re-presents narratives around political and socially significant events and because these have often been displaced, forgotten, written over, or erased - its significant for me to reintroduce a particular type of knowledge around an image. I am offering new or revised points to examine on a continuum of history that has been and continues to be manipulated and contrived in various ways. My work investigates the social, political and historical contexts that inform readings of the landscape and its contents. I am also motivated by the nature of the archive by using photography as a kind of philosophical tool to uncover and re-contextualise moments that have been overlooked or displaced.

© Ann Shelton, Wastelands, A ride in the darkness, Installation View, McNamara Gallery, New Zealand, 2010

You also regularly produce artist books and have worked creatively with newsprint material as well. Do you feel your work translates differently in book or pamphlet than on the gallery wall, and then, how do you negotiate these differences when making design decisions for your books and pamphlets?

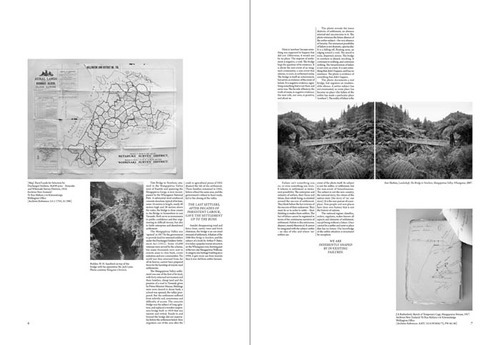

AS: For me, as I touched on above, the book is a kind of expanded field for a photograph. It’s where the crucial context comes into play, where you can write or have writing activate images. Publications also last for longer: they are the remains of the exhibition. But beyond that for me it is really about developing the conceptual and contextual aspects of a given project. For example I made a newspaper with writer and collaborator Stephen Turner, one of our intentions was to discuss media narratives in relation to history and its construction. As a result the newspaper we made included doubled texts for each photograph, one taking the journalistic approach and the other having more of a propositional or philosophical tone. These concepts were developed out of a discussion around the work with Duncan Munro the designer and Turner, both were key protagonists in the development of the format of the publication.

© Ann Shelton and Stephen Turner, Double page spread Wastelands newspaper, 2010

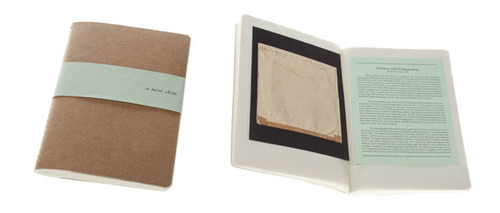

In another example I was commissioned by the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery to produce an artist book for the exhibition a library to scale (the scrapbook project Jan Bryant discusses above). I decided to use a Moleskine journal as a kind of shell or case for the book. Using Derrida’s concept of ‘a new skin’ I repositioned selected pieces of information into the journal, binding them “anew” and re-presenting them cut and pasted in a new arrangement and with a new relationship to each other.

© Ann Shelton, A New Skin, Artist Book, 2007

© Ann Shelton, Metadata, Artist Book, 2011

As this interview series focuses on artist/educators, could you describe the photography program at your institution?

AS: We have a stand-alone qualification for photography. It’s a BDES HONS degree completed over four years, then we have a MFA over 2 years and a PHD. We also have a BFA that is focused on interdisciplinary fine arts practice. Undergrad students can decide if they want an intensive and specifically photographically focused education to opt for the BDES HONS. Within this they can practice within the full-expanded field of photography from the commercial end of the spectrum to a documentary or fine arts driven focus. Upon completion of their undergrad, students can progress to an MFA Design or MFA Fine Arts and on to a PHD, again they can focus on photography at both these levels.

What kind of works are your students engaging in? Do you see their work/research as following in the same path as your own as a student, or do you see differences in how students approach the study and practice of photography today?

AS: The vast majority of my undergrad students are from what has been recently called the “Diamond Generation” by Hans Ulrich Obrist and Simon Castets. The Diamond Generation are those born post 1989, they are digital natives (something hugely important in and of itself), they are insanely well connected through social networking and they have a fundamentally different way of engaging with information and images – think multiple screens open on the computer, Facebook, Twitter, a movie – and their latest project. I think the way students approach photographic practices has been fundamentally transformed.

Growing up in New Zealand my generation were obsessed with leaving this country; with discovering the potentiality of the world outside of our geographical isolation. Technology has changed our relationship with the world, but the physical aspects of geographical displacement remain. My students are also very outward looking, they are generous and kind in a way my generation wasn’t and they are diverse in a way my own peers, as a student, were not.

By contrast my photographic education was technologically driven, prescriptive and multiple assignment based (before I went to art school, I did a one year qualification in photography and became a photo journalist). This style of education wasn’t necessarily a bad thing, it meant a very firm foundation in technique, however it’s a total paradigm shift to consider how students operate today with access to so much information, a plethora of methodologies, overlapping genres and complex thematic’s to work with.

I have incredible students, I enjoy supporting them beyond their education where I can. I like the facilitation aspect of teaching and the way it allows me to support significant futures. My students articulate positions that have not previously been heard, they make works that occupy new spaces and encompass new approaches. Many of these are mediated through the lens of technology, its shifts and transformations.

Do you have a particular student (or group of students) whose work you would like to highlight in relation to the above?

AS: I would like to discuss the work of two recent graduates, undergraduate student Daniel Betham and Masters graduate Shaun Waugh. Their practices both engage with photography in a transitional moment.

Waugh is interested in the medium as a point at which to generate discourse, his latest works (see below) take film and paper boxes as subject matter. Using digital colour-matching technologies, Waugh generates an interior for the box as photographic print, which is perfectly colour-matched to the exterior. I’m interested in Waugh’s ability to generate data about the medium and use that as material to drive an artwork. It’s a very digital idea, something that would take many hours in the dark room and would perhaps never be achieved to the level of perfection attained here. In these images photographic branding meets a kind of abstraction.

© Shaun Waugh, Fuji green, Kodak yellow, Agfa silver, 2013, found film box with archival pigment inkjet

In other works illustrated below, Waugh photographs covenanted pieces of bush in his home stomping ground of Taranaki, New Zealand, again he uses selection tools to generate colour data that isolates and articulates those spaces in a new way. There is a digital elevation of planar space, making the covenant space more significant through its deletion and replacement. Generated from the Macbeth ColorChecker chart, with a colour calibration target of 24 painted patches that is intended to mimic the spectral reflectance’s of natural objects, the colours Waugh presents here are specific, never arbitrary.

© Shaun Waugh, Covenant cut-out, yellow, 2013

Daniel Betham makes photo/video sculptures. He “employs ordinary found materials to create absurd constructions or scenarios that investigate the possibility for a spiritual encounter or enlightenment in the face of a potentially vacuous contemporary existence. [5]

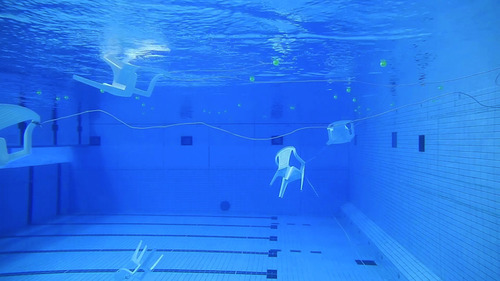

© Daniel Betham, What Would I Do Without You (1), 2012 Film Still

Betham’s work is compelling because he looks at what might seem like incongruous elements, the nexus of spirituality and a fast paced contemporary life using moving image technology and in some instances, elements of simple visual trickery.

His works operate like a kind of modern day meditation device. They feature everyday objects being used in new and elliptical ways – in one work a man lays across an office chair face down and is spinning in a 360 degree circle, while perched atop a board meeting table. All the while he laughs freakishly. In other entropic and mesmerising works such as ‘Be Here Now’, 2011 Betham’s model pours buckets of water over himself again and again while standing in the pitch-black night sea.

Betham describes his constructions as “positive transcendental sculptures, assembled in order to aid in the delivery of a form of personalised positive psychology or learned optimism” he states the “works question the possibility of finding fulfillment through capitalist ‘anything is possible’ doctrine.” [6] Read through this lens, Be Here Now, 2011 and its slow-motion blow-by-blow of what one imagines to be extremely cold water as it hits the screaming model’s body is disturbing to watch at best, conveying the idea of a kind of frightening eternal capitalist baptism.

© Daniel Betham, What Would I Do Without You (2), 2012, looping video

Lastly, do you have any particular influences within the visual arts, literature, music, philosophy, etc. that you’d like to mention in closing?

AS: More recently those influences would include: Tacita Dean, Joachim Koester, Jeremy Deller, Ariella Azoulay, Simon Schama, Ulrich Baer, Bryan Ladd, and historically: Ricky Maynard, The Fox Boy by Peter Walker, Mark Adams, Douglas Gordon, Felix Gonzales Torres, Roni Horn, Michel Foucault, Martin Jay, Geoffrey Batchen, Jonathan Crary. Among this group I should also mention a room of wall to wall history and religious narrative paintings in the Accademia Galleries in Venice. I make a pilgrimage to see these huge canvases whenever I am lucky enough to get to Venice and I guess they are important to me, as I see them as somehow being part of a progression from presence to absence in contemporary photography at the end of the last millennium.

---

LINKS

Ann Shelton

New Zealand

NOTES

[1] - Jonathan Crary, Techniques of the Observer: On Vision and Modernity in the Nineteenth Century (Cambridge, Massachusetts, and London, England: October Books, MIT P, 1996), 48-50.

[2] - The Brooklyn Rail Retrieved 16th April 2013.

[3] - In The sound of the past being sliced apart — Jan Bryant. Ann Shelton citing Jacques Derrida, Archive Fever, Chicago Press, Chicago, 1995.

Retrieved 13 May 2013. This essay was first published by the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery in 2007 in Ann Shelton: a new skin.

[4] - IBID, The sound of the past being sliced apart — Jan Bryant.

[5] - Daniel Betham, email correspondence with the artist, 16 April 2013.

[6] - IBID.

share this page