Often an uncritical (or detached as much as possible) eye seems to be the best way to represent reality. In its extreme clarity, your series Terraria Gigantica, dedicated to the world’s largest indoor landscape complexes, seems to communicate a clear idea, if not a clear opinion, with respect to the relationship between nature as an object and man as a dominant player…

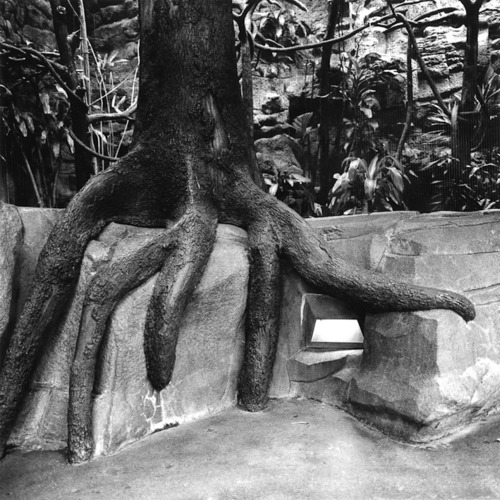

Dana Fritz (DF) My opinion about the human-nature relationship has evolved significantly because of this project. At first I saw them as more oppositional but now believe it is too late for the idea of defining nature by our absence. As Bill McKibben, William Cronon and Michiel Schwartz point out (in very different approaches,) we have fundamentally altered the planet and using “wilderness” as the reference point for nature is not useful to move forward. The giant terrariums serve as complex symbols for where we are now and I have grown to appreciate them for their inherent strangeness as well as their scientific and educational value. While Biosphere 2 had a somewhat dubious original mission, all these sites are now focused on education and in some way on research. I do still wonder if visits to them supplant time spent out of doors for some people, especially children. (In Last Child in the Woods, Richard Louv writes about the detrimental effects of children not playing outside.) However, because of their emormous scale and density of plants, these sites produce a sense of wonder in visitors that may lead to future interest in the natural world. Being in these vivaria, one feels small yet awestruck (and perhaps even empowered) that humans can build and maintain such a place. I am fascinated by the structural elements of the architecture and landscape design and the combination of live plants and often indistinguishable artificial (but mimetic) elements such as plants and rocks that make up the exhibits. Within all of this structure, seemingly unplanned natural systems arise such as when a bird from outside builds a nest or when green slime develops on walls. All of the sites I photograph are educating visitors about our altered world and the important role we all play in it. While I applaud these efforts, I have to wonder if most visitors consider the philosophical implications of such large scale displacement and elaborate simulation. These are some of the many issues that I consider when making photographs.

© Dana Fritz from the series 'Terraria Gigantica'

© Dana Fritz from the series 'Terraria Gigantica'

© Dana Fritz from the series 'Terraria Gigantica'

© Dana Fritz from the series 'Terraria Gigantica'

© Dana Fritz from the series 'Terraria Gigantica'

© Dana Fritz from the series 'Terraria Gigantica'

Assuming that the natural landscape is a concept that is almost never reflected anywhere in the world, as every known landscape for good or for bad is the result of human intervention within nature. What is the difference between a cultivated field or a hill redesigned with vineyards and an architecture of steel and glass in the Arizona desert?

DF: This is a great question. I suppose the obvious difference is that the places I photograph are enclosed on all sides including the top by building materials rather than bound by fences or roads. Thus, they are nearly closed systems that are far less effected by the uncontrolable aspects of weather. But really it is more just a matter of degree. Is the vineyard part of a biodynamic natural system or full of cloned grapes and synthetic pesticides and fertilizers? Is the Eden Project, whose domes are full of non-native but organically grown plants, more natural than the outdoor vineyard of clones? In Next Nature Michiel Schwarz asserts “…what is nature and what is not may not be the real issue.” He goes on to write that…“‘nature so-called’ can shift our attention to one of the key questions in cultural environmental politics: What kind of nature do we want?”.

© Dana Fritz from the series 'Terraria Gigantica'

© Dana Fritz from the series 'Terraria Gigantica'

Your unique way of investigating the liminal spaces where the natural and artificial elements collide, uses the detail as the ideal tool to capture more clearly the discontinuities and imbalances of these “contained” landscapes. Is grasping what is illusory or simply that which is not entirely in focus also a matter of scale?

DF: The idea of scale is very interesting because it was the deciding factor in the sites I chose to photograph. Perhaps it is paradoxical that I chose the world’s largest enclosed landscape complexes but mainly focus on details or vignettes to explore my questions about nature. In choosing them, I speculated that such grand efforts would reveal strange juxtapositions of natural and artificial because, at some point, the facade of naturalness must give way to the artificiality of the enclosure. While anything at a large scale seems to attract attention, I wonder if we only begin to understand more deeply when we look more closely at details. Perhaps then we might see “the big picture".

© Dana Fritz from the series 'Terraria Gigantica'

© Dana Fritz from the series 'Terraria Gigantica'

In a some of the images of Terraria Gigantica we have the impression that these enormous architectures are always more fragile than the natural elements, as if comparing a pillar of steel to a branch or a leaf, the first reveals its true ephemeral nature. It seems that at every human “progress” nature takes its counter-measures, sometimes anticipations, to confirm its persistence. Is the domination of nature only an illusion for humans?

DF: This, too, is a question that comes up in these sites. I began photographing Biosphere 2 when it was languishing somewhat and before the University of Arizona had taken over. Some parts of it looked a bit shaggy as if the plants were gaining on the architecture and the biomes were going wild in the absence of regular maintenance. Even now with a larger staff of caretakers and research going on, there are still a few spots, mainly in the rain forest, where it seems the building is still vunerable to a plant takeover. I find these areas particularly fascinating (even strangely hopeful) and they are the subjects of several images in the series. Of course all of these things lead to bigger questions about how we live and the future of life on our planet. We seem to be dominant until struck by an earthquake or a flood or even an outbreak of disease. In The World Without Us, Alan Weisman describes how quickly most of our built environment would crumble and erode from natural forces including weather and plants if humans suddenly disappeared. He makes it seem that a return to the wild is not only possible, but eminent if only we got out of the way.

© Dana Fritz from the series 'Terraria Gigantica'

© Dana Fritz from the series 'Terraria Gigantica'

© Dana Fritz from the series 'Terraria Gigantica'

© Dana Fritz from the series 'Terraria Gigantica'

Compared to these concepts of the natural and the artificial, your Garden Views series seems to deepen the topic from a more formal point of view. The choice of black and white goes in the direction of a more conscious de-naturalization of the eye devoted to gardens as a purely cultural expressions. After centuries of tamed nature, are we really confident that our need for nature is authentic?

DF: Edward O. Wilson and others have written extensively about biophilia (the instinctive bond between humans and other living systems) and while I can’t speak for others, I do believe that my need for some kind of nature is authentic and visceral. However, some of this can be experienced on a walk or bicycle ride through my neighborhood when I feel the warmth of the sun on my skin and the fresh air in my lungs. But it occurs to me that neither of these experiences are visual or constructed (and neither could occur for the Biosperians who were locked in Biosphere 2 from 1991 to 1993.) I get a great deal of satisfaction from growing a vegetable garden, watching the songbirds in my yard and raptors in the park across the street, visiting a farm to buy food, strolling through a centuries old Japanese or Italian garden and hiking in the desert. Each of these activities occupies a different point along the nature-culture spectrum. In regard to the formal gardens in Garden Views, perhaps we (at least historically) have had an authentic need to engage with natural materials and processes that we can manipulate, but that still grow and change sometimes unpredictably. Once we have shaped them, they call us back to keep them in shape or remind us of our failure to do so. Gardens result from a human-nature relationship that is satisfying to both the gardener and the visitor, and perhaps even the plants themselves if you consider Michael Pollan’s concepts of human and plant co-evolution in the Botany of Desire. We need them for nourishment and cultural expression and they need us to reproduce.

© Dana Fritz from the series 'Gardn Views'

© Dana Fritz from the series 'Gardn Views'

© Dana Fritz from the series 'Gardn Views'

© Dana Fritz from the series 'Gardn Views'

LINKS:

share this page